Lacking tools and technologies modern architects take for granted, an ancient people created one of the Seven Wonders of the World.

The god-king’s legacy is complete. The immense life-giving river that flows nearby – later to be called the Nile – has by now had people farming its banks for about two and half millennia.

Like almost every pyramid, the Great Pyramid of Giza rises from the Nile’s west bank, the place where the sun ‘dies’ each evening.

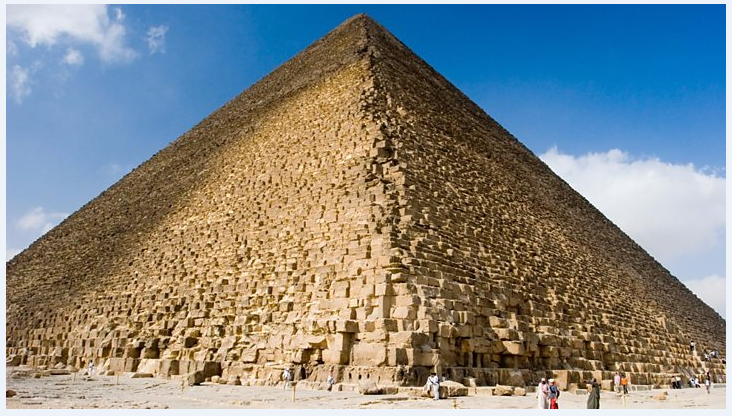

Later visitors will see an exterior of ascending ocher-brown bricks, for its outer surface of reflective limestone will have long ago been stripped away.

Today it gleams white in the sunshine.

What will one day be called the Great Pyramid of Giza is located on a plateau, south of the future city of Cairo.

Paintings and postcards will later on create an impression of windswept loneliness, where pyramids set amid uninhabited desert.

Pyramid of Khufu

In reality, both then and now, the structure looms over a sprawl of human activity.

For over twenty years, thousands of men have labored to get around 2.3 million blocks in position at a rate of around 300 stones per day.

Contrary to later myth, these people are not slaves sweating under the whip, but paid workers, some of whom possess specialist skills.

Two settlements rise nearby, one for permanent workers and their families, the other for the migrants who work here for a few months at a time.

The god-king is called Khufu, although he will also be known as Cheops.

Around seven centuries before his birth, the unification of a southern and northern kingdom had created a dynasty with mighty pharaonic rulers at the helm.

In this time, the Early Dynastic period has given way to what will be called the Old Kingdom.

What was the first Egyptian pyramid?

It was the Old Kingdom pharaoh Djoser who ordered the building of the first ‘step’ pyramid at Sakkara, 20 kilometers south of here.

That design, involving receding platforms, was the work of Imhotep, one of the few Egyptians – besides the pharaohs themselves – who will one day be venerated as a god.

As vizier (chief official) to the pharaoh, Imhotep also excelled as an astronomer and physician. In the latter capacity he wrote a text that describes the treatment of over 200 illnesses.

But not even a god-king is spared his or her mortality. That, above all, is the purpose of the pyramid.

What was the Great Pyramid of Giza used for?

The pharaoh’ soul is destined to reach an after-world called Sekhet Aaru (meaning ‘the Field of Reeds’). If his soul so chooses, he can return to earth, the apex of the pyramid serving as a beacon.

When the Great Pyramid of Giza is complete, its base covers 13 acres and its summit rises to 481 feet (147 meters).

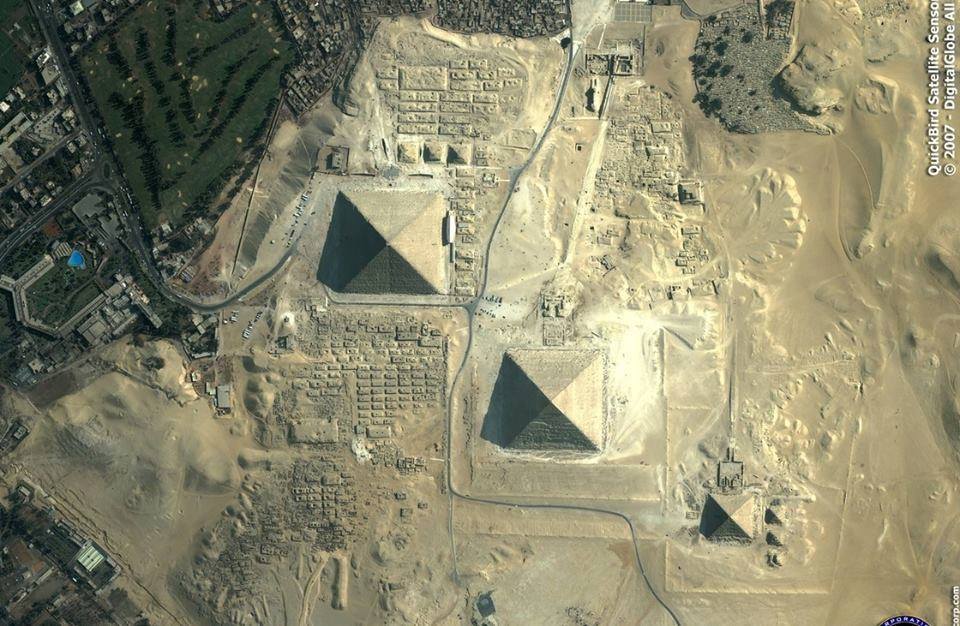

Within a few decades, two of Khufu’s successors, Khafre and Menkaure, will have left pyramids of their own a few hundred meters away, together with a massive reclining sphinx statue.

The three Giza pyramids, their sides perfectly aligned to face north, south, east and west, will dwarf all others built before or after.

Like all the pharaohs, Khufu has been planning his ‘house of eternity’ since ascending the throne.

As the intermediary between the gods and mortals, it is believed he will become Osiris, god of the dead upon dying.

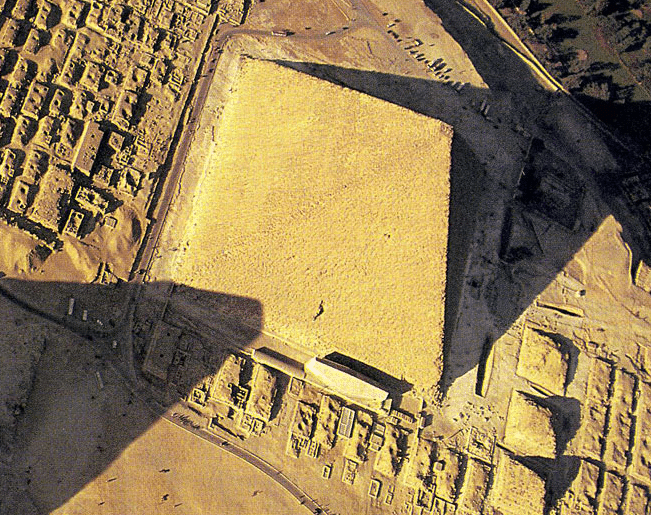

And to expedite the passing of the pharaonic soul, the pyramid has been set within an expansive complex.

Who was buried in the Great Pyramid of Giza?

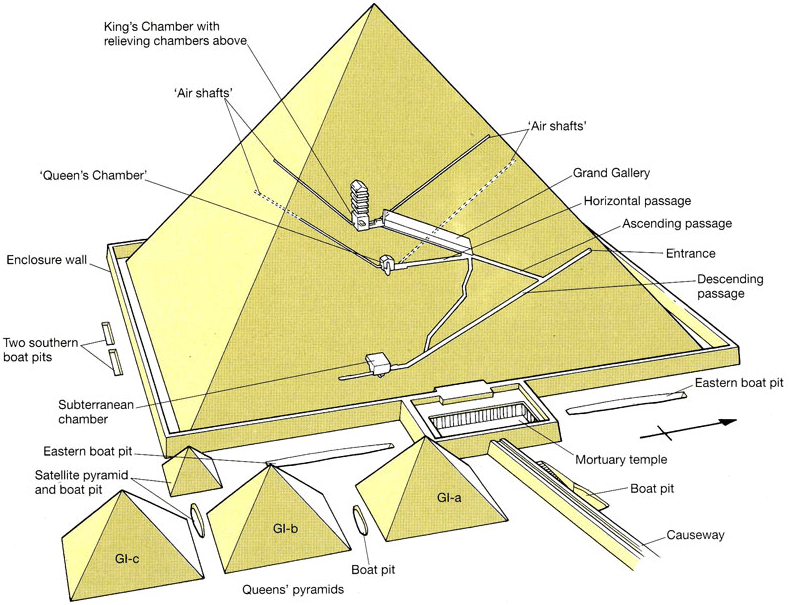

Khufu’s funeral will begin in a temple in the adjacent valley from where his body will be transported by priests to the pyramid along a causeway.

There is a mortuary temple where his body is worshiped and three smaller pyramids for his queens.

Meanwhile, noblemen will be buried in nearby mastaba (bench) tombs, the standard Egyptian tomb during the Early Dynastic period

Upon his death, Khufu’s great solar barge, 143 feet by 19 feet (43 meters by 5.7 meters), is buried in a deep pit for his use in the afterlife.

Within the pyramid itself are ascending and descending passages, shafts for the possible purpose of ventilation and at least three chambers.

Future explores will find a subterranean chamber, apparently never used.

Above this is a room, later to be misleadingly called the Queen’s Chamber, which was likely used as a store for the pharaoh’s funerary gifts.

Highest of all is the King’s Chamber, its roof supported by granite beams, each weighing 50 tons and designed to deflect the weight of the masonry above.

Here, almost in the center of the pyramid, the pharaoh’s mummified corpse is placed within a granite sarcophagus. But sometime in the ensuing 45 centuries it will be lost, or even perhaps stolen by tomb raiders.

The god-king’s legacy, the last surviving Wonder of the ancient world, survives. Of the god-king himself, there is nothing.

Who actually built the pyramids?

The popular image of the pyramid’s construction involves immense lines of wretched labourers dragging vast blocks along with an encouraging lash from the slave-driver’s whip.

The Flight from Egypt is described in the Old Testament’s Book of Exodus.

The Greek historian Herodotus visited Egypt around 450 BCE and surmised that the Giza pyramids were built by 100,000 slaves “who labored constantly and were relieved every three months by a fresh gang.”

In 1888, British archaeologist Flinders Petrie, examining the Middle Kingdom pyramid at Lahun, found the remains of a laborers’ town.

Its encircling walls suggested the laborers were captives. Slavery did exist during the various dynasties.

However the estimates of Herotodus are wrong: it is more likely that the Giza pyramids were built by around 5,000 primary workers (quarry workers, hauliers and masons) augmented by another 20,000 secondary workers (ramp builders, mortar mixtures, artists, cooks, wood suppliers).

Egyptologist Mark Lehner, an associate of Harvard’s Semitic Museum, did research during the Nineties at Giza, and eventually discovered two settlements southeast of the Great Pyramid.

One was laid out in an organic fashion, suggesting it grew over time. The other town was laid out in a grid fashion, bounded to the northwest by a great wall, known today as the ‘wall of the crow.’

The grave of a pyramid builder was inadvertently discovered by a tourist in 1990.

A decade later, the nation’s chief Egyptologist Zahi Hawass announced the discovery of laborers’ remains in grave pits near the pyramid, which would have been an unlikely privilege for a slave.

Although not mummified, the dozen skeletons were buried in fetal positions, heads pointing west and feet pointing east, in the traditional Egyptian fashion.

These workers had bread and beer placed in the pits, offerings for the afterlife.

Graffiti within the pyramids have been signed by crews such as the ‘Friends of Khufu’ or the ‘Drunks of Menkaure,’ pointing to a team ethic and the likelihood of specialised work groups.

How were pyramids built step by step?

The pyramids were preceded by tombs called mastabas (an Arabic word meaning ‘bench’), which consisted of an underground burial chamber and overground chapel.

These mastabas first seem to have appeared some time around 3500 BCE, during a time when mummification techniques were also in the process of being perfected.

By the Third Dynasty of the Old Kingdom, pharaoh Djoser had sufficient wealth to commission the first ‘step’ pyramid atop an existing mastaba.

But it was under Khufu’s father Snefru that the first true pyramids appeared.

His earliest pyramid at Maydūm was originally a step pyramid, but it collapsed after attempts at modifications.

Of his two later pyramids at Dashūr, structural faults left the Bent or Blunted Pyramid with its characteristic incline. Later, the Red Pyramid was successfully built as a true pyramid.

The lessons of Maydūm and Dashūr impressed upon Khufu’s engineers the importance of getting the foundations right: the base of the Great Pyramid is level to two centimeters.

To achieve this, the workers may have poured water into the excavated site and leveled everything above the waterline.

They would then lower the water level, removing more material until the foundation was level.

The pyramids were made of limestone, granite, basalt, gypsum and baked mud bricks. In the case of the Giza pyramids, limestone blocks were quarried at Giza and probably a few other sites.

The granite stones may have been brought up the Nile by barge from Aswan, and basalt was sourced in the nearby Fayoum depression.

The blocks would have been carved away using copper or stone tools. Transporting them to the building site would have presented serious challenges and is a source of much speculation today.

To move some of the larger blocks by barge, canals may have been dug. Most blocks were probably dragged overland on wooden sleds with ropes.

Alternatively, blocks may have been placed atop wooden rollers or within circular containers to be rolled along like a beer keg.

When the blocks arrived at the site, there would have been several thousand workers there: some skilled craftsmen, some labourers, some locals and some from outlying provinces.

Getting the blocks up and into position involved building a series of ramps upon inclined planes of mud, brick and rubble.

As the pyramid grew taller, the ramp had to be widened and extended or else it would collapse.

Since the core of a true pyramid was essentially a step pyramid with packing blocks laid on top, the ramps would not have approached it at right angles; instead they ran from step to step.

American Egyptologist Mark Lehner speculates that a spiraling ramp may have begun in the stone quarry to the southeast and continued around the pyramid.

The blocks were drawn into place along on sleds that were lubricated by water or milk. More recently, the French Egyptologist Jean Pierre Houdin has used 3D imaging to identify an anomalous spiral structure within Khufu’s pyramid.

Houdin proposes a theory based around an internal ramp: a regular external ramp was used for the first 30 per cent of the pyramid, then a spiralling internal ramp transported the blocks beyond that height.

Levering methods would have complemented the ramp structure.

The blocks may have been lifted incrementally, using wooden wedges to gradually move the stones upwards. It would have been a tremendous feat.

The Great Pyramid of Giza: An enduring mystery

The end result was a structure that was symbolic on many levels.

The pyramid’s sloping limestone walls are representative of the descending rays of the sun, and its north pointing shaft points to the area of the night sky around which the stars rotate.

A modern visitor entering Khufu’s pyramid does so through the so-called ‘Robbers’ Tunnel’.

In 820, the Arab Al-Ma’mun led his men on a tomb raid. The men expected to find treasure, but Al-Ma’mun himself was intrigued by a legend that the pyramid contained a book of limitless historical knowledge.

To get inside, they used brute force. They used fire and battering rams to gain entry.

Previously, in a fit of religious fanaticism, the sultan of Egypt, Al-Aziz Uthman (1171-1198), had attempted to demolish Khufu’s pyramid.

He failed, due to the scale of the monument, although damage was done to Menkaure’s pyramid, and in many ways the pyramid remains impenetrable even today.

Despite valid theories and advanced imaging technologies, much about its construction and purpose will probably always be mysterious.

However, built with mostly voluntary labour and rudimentary technologies, apparently in tribute to a single human, it has far outlived the ancient civilization that produced it.

In four millennia from now, who can know whether the same will be said of today’s great buildings?

News

Unveiling the Ingenious Engineering of the Inca Civilization: The Mystery of the Drill Holes at the Door of the Moon Temple in Qorikancha – How Were They Made? What Tools Were Used? What Secrets Do They Hold About Inca Technology? And What Does Their Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of Ancient Construction Methods?

In the heart of Cusco, Peru, nestled within the ancient Qorikancha complex, lies a fascinating testament to the advanced engineering prowess of the Inca civilization. Here, archaeologists have uncovered meticulously angled drill holes adorning the stone walls of the Door…

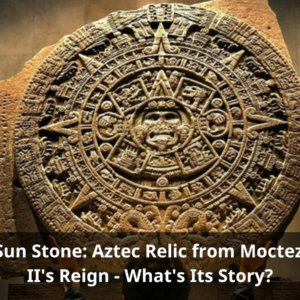

Unveiling the Sun Stone: Aztec Relic from the Reign of Moctezuma II (1502-1520) – What Secrets Does It Hold? How Was It Used? What Symbolism Does It Carry? And What Does Its Discovery Reveal About Aztec Culture?

In the heart of Mexico City, amidst the bustling Plaza Mayor, lies a silent sentinel of ancient wisdom and artistry – the Sun Stone. This awe-inspiring artifact, dating back to the reign of Moctezuma II in the early 16th century,…

Uncovering the Past: Rare 1,000-Year-Old Copper Arrowhead Found – Who Crafted It? What Was Its Purpose? How Did It End Up Preserved for So Long? And What Insights Does It Offer into Ancient Societies?

In the realm of archaeology, every discovery has the potential to shed light on our shared human history. Recently, a remarkable find has captured the attention of researchers and enthusiasts alike – a rare, 1,000-year-old copper arrowhead. This ancient artifact…

Unveiling History: The Discovery of an Old Sword in Wisła, Poland – What Secrets Does It Hold? Who Owned It? How Did It End Up There? And What Does Its Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of the Past?

In a remarkable archaeological find that has captured the imagination of historians and enthusiasts alike, an old sword dating back to the 9th-10th century AD has been unearthed in Wisła (Vistula River) near Włocławek, Poland. This discovery sheds light on the rich…

Unveiling the Hidden Riches: Discovering the Treasure Trove of a Notorious Pirate – Who Was the Pirate? Where Was the Treasure Found? What Historical Insights Does It Reveal? And What Challenges Await Those Who Seek to Uncover Its Secrets?

A group of divers said on May 7 that they had found the treasure of the infamous Scottish pirate William Kidd off the coast of Madagascar. Diver Barry Clifford and his team from Massachusetts – USA went to Madagascar and…

Excavation Update: Archaeologists Unearth Massive Cache of Unopened Sarcophagi Dating Back 2,500 Years at Saqqara – What Secrets Do These Ancient Tombs Hold? How Will They Shed Light on Ancient Egyptian Burial Practices? What Mysteries Await Inside? And Why Were They Buried Untouched for Millennia?

Egypt has unearthed another trove of ancient coffins in the vast Saqqara necropolis south of Cairo, announcing the discovery of more than 80 sarcophagi. The Tourism and Antiquities Ministry said in a statement that archaeologists had found the collection of colourful, sealed caskets which were…

End of content

No more pages to load