Funerary Mask of Psusennes I

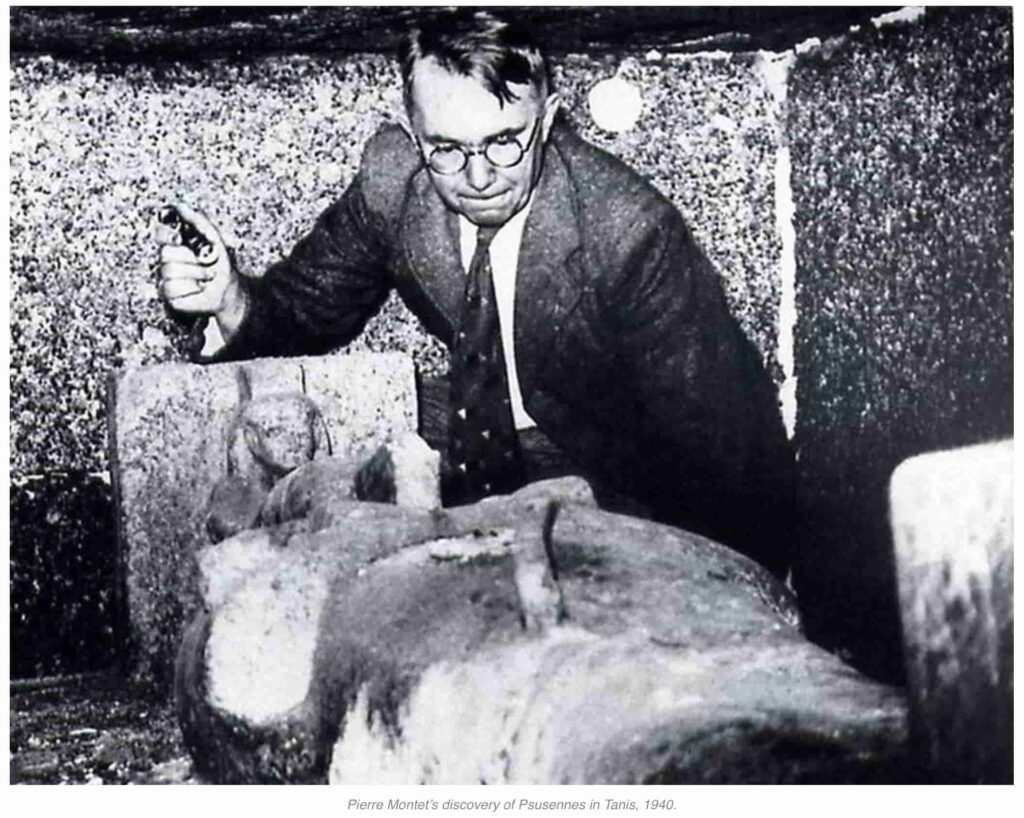

The Psusennes I mask is the gold funerary mask of Pharaoh Psusennes I (1047-1001 BC) of the 21st Dynasty. It was discovered by French Egyptologist Pierre Montet in February/March 1940 in the Tanis necropolis and is currently housed in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo.

In the royal burials of Tanis, a total of four funerary masks were found, all made of gold, belonging to Pharaohs Psusennes I (Hellenized version of the original Egyptian Pasebakenniut), Amenemope (1001-992 BC), Sheshonq II (887-885 BC), and General Uendjebauendjed (a contemporary of Psusennes I).

On February 15, 1940, Pierre Montet found the burial chamber of Psusennes I and entered it on February 21 in the presence of King Faruq I of Egypt. A huge block of granite had to be removed in order to reach the Pharaoh’s sarcophagus.

Upon opening the great pink granite sarcophagus (stolen from the tomb of Merenptah, successor to Ramses II), the archaeologists found the Pharaoh’s majestic coffin, made of solid silver, partially damaged by the humidity of Tanis. Surrounding the sarcophagus were ushabtis.

In ancient Egypt, silver was more expensive than gold because it was less abundant. The intact mummy of the Pharaoh was adorned with various jewels (30 rings, 22 bracelets), finger covers, amulets, sandals, and a cloak, all made of gold.

The mask on the now reduced-to-a-skeleton mummy of Psusennes I is the most elaborate and richest among those found at the site, and is the second of a sovereign among Egyptian funerary masks that have survived to this day, after the famous Tutankhamen mask from three hundred years earlier, with which it is similar.

However, ancient Egypt in the 11th century BC was considerably less wealthy and powerful. While Tutankhamun‘s mask bears hieroglyphic inscriptions on the back of the breastplate with a chapter from the Book of the Dead, Psusennes I’s mask has none.

Additionally, the vitreous paste and lapis lazuli inlays are only present on the eyes and eyebrows, without highlighting the stripes of the nemes ceremonial scarf or the lines of the false beard, or the details of the large uraeo on the Pharaoh’s forehead.

Compared to the several kilograms of gold used on the first mask, the Psusennes mask was made of a sheet of gold less than a millimeter thick (0.6 mm) and the decoration was almost entirely done through incision. The aura and false beard were carved separately and applied later.

The artist gave the Pharaoh’s face an idealized youthful appearance, very different from the real appearance of Psusennes I as reconstructed from the skull, which showed an eighty-year-old man affected by arthritis and with decayed teeth.

Due to the more humid and rainy climate, the deposits in Lower Egypt are not as abundant as those in Upper Egypt, whose dry and desert environment allows for the preservation of perishable materials that are not usually preserved, such as wood, leather, textiles, papyrus, food, and even mummies.

However, even with their lesser wealth, the three royal tombs of Tanis are the only ones that have been discovered practically intact, aside from that of Tutankhamun.

Despite the importance of the discovery, the outbreak of World War II caused it to go largely unnoticed, unlike Howard Carter’s more publicized discovery.

Silver coffin of Psusennes I, Cairo Museum

Gold burial mask of King Psusennes I

2

Gold burial mask of King Psusennes I

News

Unveiling the Ingenious Engineering of the Inca Civilization: The Mystery of the Drill Holes at the Door of the Moon Temple in Qorikancha – How Were They Made? What Tools Were Used? What Secrets Do They Hold About Inca Technology? And What Does Their Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of Ancient Construction Methods?

In the heart of Cusco, Peru, nestled within the ancient Qorikancha complex, lies a fascinating testament to the advanced engineering prowess of the Inca civilization. Here, archaeologists have uncovered meticulously angled drill holes adorning the stone walls of the Door…

Unveiling the Sun Stone: Aztec Relic from the Reign of Moctezuma II (1502-1520) – What Secrets Does It Hold? How Was It Used? What Symbolism Does It Carry? And What Does Its Discovery Reveal About Aztec Culture?

In the heart of Mexico City, amidst the bustling Plaza Mayor, lies a silent sentinel of ancient wisdom and artistry – the Sun Stone. This awe-inspiring artifact, dating back to the reign of Moctezuma II in the early 16th century,…

Uncovering the Past: Rare 1,000-Year-Old Copper Arrowhead Found – Who Crafted It? What Was Its Purpose? How Did It End Up Preserved for So Long? And What Insights Does It Offer into Ancient Societies?

In the realm of archaeology, every discovery has the potential to shed light on our shared human history. Recently, a remarkable find has captured the attention of researchers and enthusiasts alike – a rare, 1,000-year-old copper arrowhead. This ancient artifact…

Unveiling History: The Discovery of an Old Sword in Wisła, Poland – What Secrets Does It Hold? Who Owned It? How Did It End Up There? And What Does Its Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of the Past?

In a remarkable archaeological find that has captured the imagination of historians and enthusiasts alike, an old sword dating back to the 9th-10th century AD has been unearthed in Wisła (Vistula River) near Włocławek, Poland. This discovery sheds light on the rich…

Unveiling the Hidden Riches: Discovering the Treasure Trove of a Notorious Pirate – Who Was the Pirate? Where Was the Treasure Found? What Historical Insights Does It Reveal? And What Challenges Await Those Who Seek to Uncover Its Secrets?

A group of divers said on May 7 that they had found the treasure of the infamous Scottish pirate William Kidd off the coast of Madagascar. Diver Barry Clifford and his team from Massachusetts – USA went to Madagascar and…

Excavation Update: Archaeologists Unearth Massive Cache of Unopened Sarcophagi Dating Back 2,500 Years at Saqqara – What Secrets Do These Ancient Tombs Hold? How Will They Shed Light on Ancient Egyptian Burial Practices? What Mysteries Await Inside? And Why Were They Buried Untouched for Millennia?

Egypt has unearthed another trove of ancient coffins in the vast Saqqara necropolis south of Cairo, announcing the discovery of more than 80 sarcophagi. The Tourism and Antiquities Ministry said in a statement that archaeologists had found the collection of colourful, sealed caskets which were…

End of content

No more pages to load