When she acceded to the throne of Egypt, Hatshepsut surrounded herself with a group of officials and priests who held the main government positions: vizier, palace superintendent, great royal architect …

Hatshepsut is often remembered as one of the few women who achieved the rank of pharaoh. She did so against all the laws and customs of the Egyptian State, taking advantage of a series of dynastic circumstances that allowed her to channel her ambition for power.

Daughter of Thutmose I and his main wife, Queen Ahmose, her marriage to her stepbrother Thutmose II made her queen consort and, after being soon a widow, assumed the regency until her stepson Thutmose III–Son of Thutmose II and one of his secondary wives– reached the necessary age to rule.

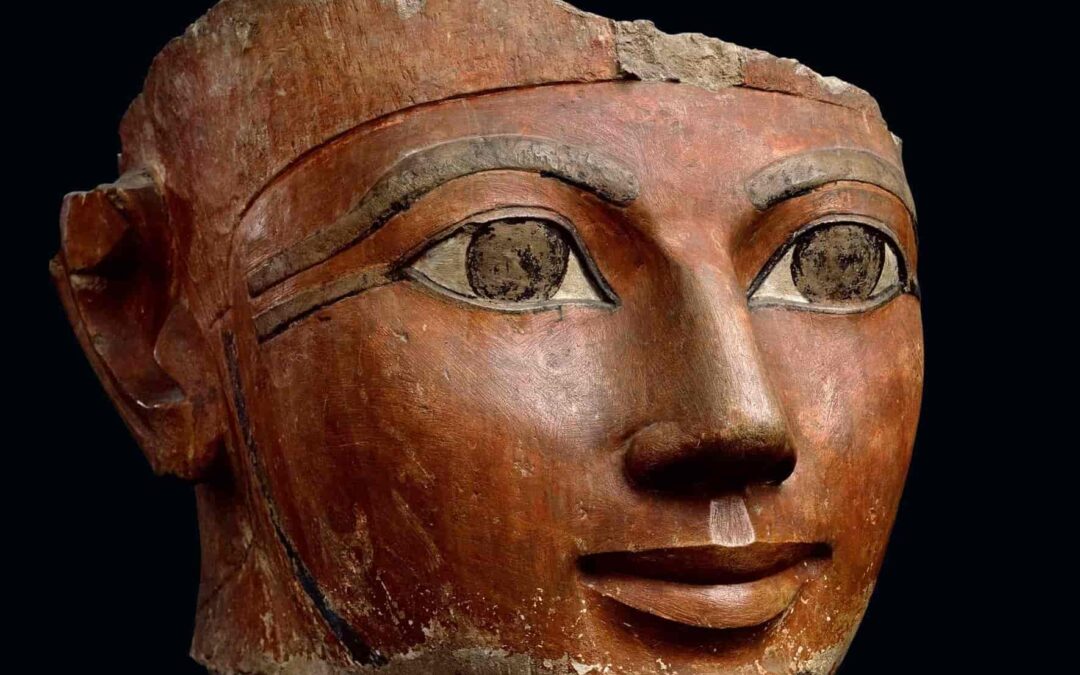

After seven years she changed her name to Maatkare Hatshepsut and began to show herself as the sole sovereign of Egypt, adopting the attributes of a pharaoh – the false beard and the nemes headdress – and the royal male epithets of King of Upper and Lower Egypt and Lord of the Two Lands.

Not even when Thutmose III came of age did Hatshepsut renounce power. Thus, for almost two decades Egypt had two pharaohs, the mother and the stepson, who reigned jointly without apparent conflict, although it was Hatshepsut who held the reins of the country.

As pharaoh, Hatshsepsut occupied the center of a brilliant court based in the country’s capital, Thebes. In it, in addition to the members of the royal family and their servants, there were a large number of courtiers and officers who performed civil, religious and military functions.

We know the names of some, such as Maya, responsible for the prophets (priests); Mentekhenu, in charge of the security of the palace, or Satepihu, in charge of the priests of Tanis.

The three most powerful characters in the Theban court, however, were Hapuseneb, Senenmut, and Djehuty.

The most important position in the Egyptian administration was that of vizier. Equivalent to a current head of government, the vizier served directly with the king and all other positions were under his responsibility.

We know that Hatshepsut had several viziers throughout her reign. She inherited the one that Thutmose II already had, Ineni, also a royal architect, whom he soon relegated. Useramum, for his part, was apparently closer to Thutmose III.

The one who played the most prominent role during Hatshepsut’s reign was undoubtedly Hapuseneb.

As high priest of Amun, administrator of the temples and head of the prophets of Upper and Lower Egypt, he assured her of the support of the powerful clergy of Amun.

He was also responsible for the construction of the tomb of the sovereign in the Valley of the Kings. Hapuseneb concentrated in his person the highest judicial power.

The enigma of Senenmut

The other great pillar of the queen’s rule was Senenmut. His father, Ramose, who already held high office with Thutmose II, introduced him to the royal court.

With Hatshepsut, Senenmut acquired numerous titles: great royal architect, head of the royal apartments, palace superintendent, butler of the God’s wife, responsible for the royal seals …

His recognition is reflected in an inscription of the temple of Karnak:

«The greatest among the great, in the whole country, one who hears what must be heard, the only one among the only ones, the steward of Amun. I am the one who enters the royal palace being loved, and when he leaves it, he is praised, rejoicing the heart of the king daily, the friend, the governor of the palace, Senenmut ». At the mortuary temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari.

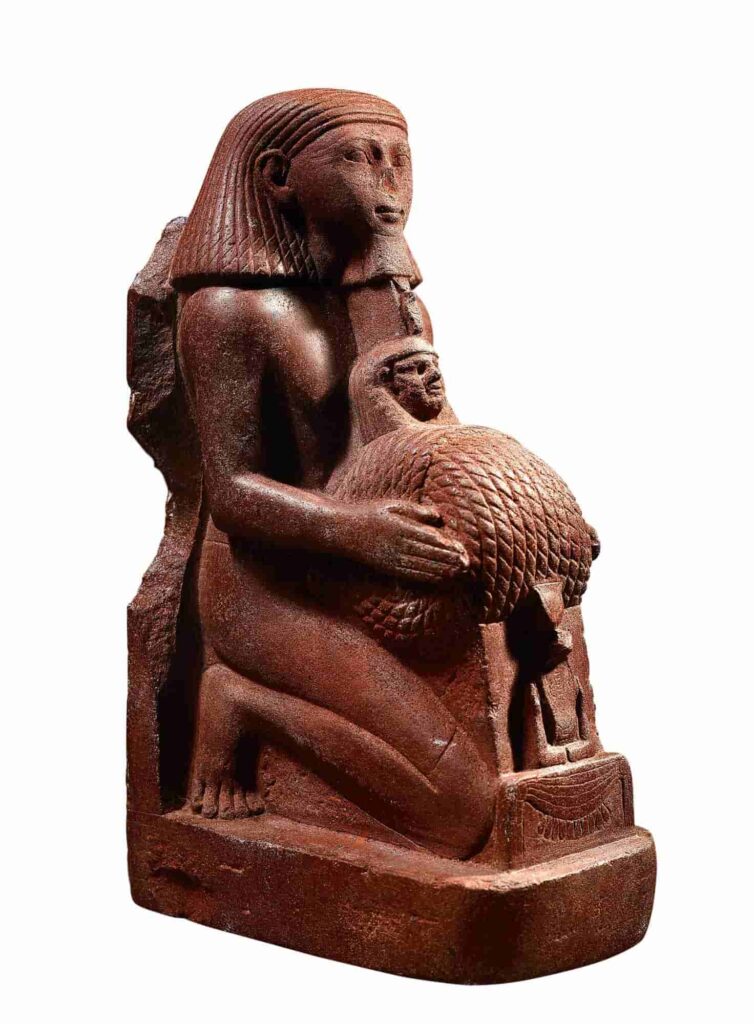

Senenmut was even the tutor of Princess Neferure, daughter of Hatshepsut, who wanted her to marry Thutmose III, a project that was frustrated by the premature death of the young woman.

It has even been speculated that Senenmut was Hatshepsut’s lover and father of her daughter, which would explain the granite sculptures in which he appears accompanied by the princess.

However, from the year 19 of the reign of Hatshepsut, the name of Senenmut disappears from the texts; perhaps he had died or fell from grace by supporting Thutmose III in the final phase of the Hatshepsut’s reign.

Another important personage in the court of Hatshepsut was Djehuty, who held the positions of great royal architect, supervisor of the works and supervisor of the treasury.

Djehuty directed the artisans in charge of the temples in Thebes; He participated in the construction, expansion and renovation of numerous monuments in Egypt and Nubia, and was in charge of registering and accounting for the exotic products brought from the country of Punt, which Hatshepsut had on the walls of her temple.

Djehuty was also in charge of decorating the temples of Karnak and Deir el-Bahari with large copper doors, he also had two large granite obelisks brought from the quarries of Aswan to the temple of Karnak under the supervision of Senenmut.

In the reliefs of the first terrace of the temple of Hatshepsut these obelisks are shown on the deck of a ship at the time of their transport.

Erased from history

Still other Hatshepsut officials could be cited. For example, the great commercial and diplomatic expedition to the country of Punt, which consisted of five ships and 210 men, was led by Nehesy, an officer of Nubian origin who held the positions of royal messenger, bearer of the royal seal and chancellor of the north.

Nehesy had the mission of negotiating with the rulers of that territory, and in particular with the chief Parehu and his wife Ivy, as seen in the reliefs of the temple of Deir el Bahari.

Since Hatshepsut died around the 22nd year of her reign, a blanket of silence fell over her figure.

The woman who had dared to proclaim herself pharaoh was the object of a “damnatio memoriae”, the elimination of all reference to her reign, as if it had not taken place; even her name was removed from the List of Kings.

Traditionally it was thought that the culprit had been Thutmose III, but subsequent investigations have shown that the operation was carried out gradually, especially during the 19th and 20th dynasties.

It would be the European scholars of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as Champollion, Naville, or Carter, who would rescue the memory of the great queen of the New Kingdom.

Senenmut, Louvre Museum, Paris.

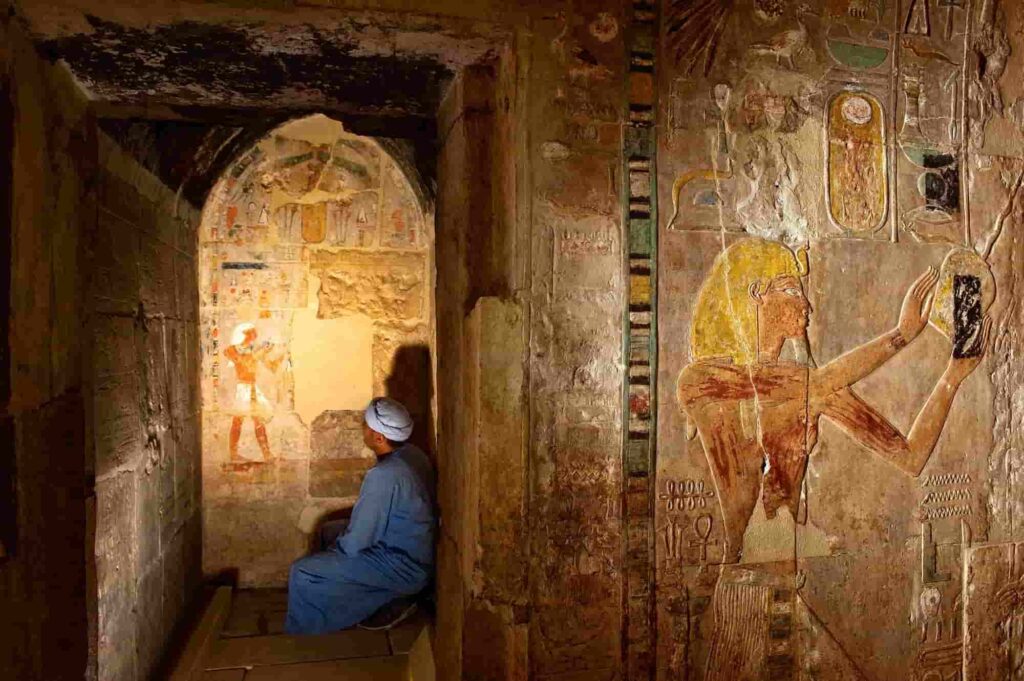

The Chapel of Amun Ra. Hatshepsut’s funerary temple at Deir el-Bahari contained several chapels dedicated to the gods. On the left, the one dedicated to Amun Ra.

News

Unveiling the Ingenious Engineering of the Inca Civilization: The Mystery of the Drill Holes at the Door of the Moon Temple in Qorikancha – How Were They Made? What Tools Were Used? What Secrets Do They Hold About Inca Technology? And What Does Their Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of Ancient Construction Methods?

In the heart of Cusco, Peru, nestled within the ancient Qorikancha complex, lies a fascinating testament to the advanced engineering prowess of the Inca civilization. Here, archaeologists have uncovered meticulously angled drill holes adorning the stone walls of the Door…

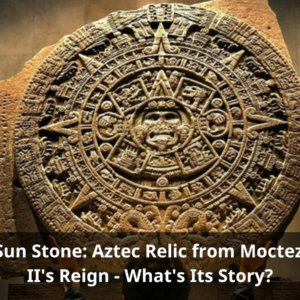

Unveiling the Sun Stone: Aztec Relic from the Reign of Moctezuma II (1502-1520) – What Secrets Does It Hold? How Was It Used? What Symbolism Does It Carry? And What Does Its Discovery Reveal About Aztec Culture?

In the heart of Mexico City, amidst the bustling Plaza Mayor, lies a silent sentinel of ancient wisdom and artistry – the Sun Stone. This awe-inspiring artifact, dating back to the reign of Moctezuma II in the early 16th century,…

Uncovering the Past: Rare 1,000-Year-Old Copper Arrowhead Found – Who Crafted It? What Was Its Purpose? How Did It End Up Preserved for So Long? And What Insights Does It Offer into Ancient Societies?

In the realm of archaeology, every discovery has the potential to shed light on our shared human history. Recently, a remarkable find has captured the attention of researchers and enthusiasts alike – a rare, 1,000-year-old copper arrowhead. This ancient artifact…

Unveiling History: The Discovery of an Old Sword in Wisła, Poland – What Secrets Does It Hold? Who Owned It? How Did It End Up There? And What Does Its Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of the Past?

In a remarkable archaeological find that has captured the imagination of historians and enthusiasts alike, an old sword dating back to the 9th-10th century AD has been unearthed in Wisła (Vistula River) near Włocławek, Poland. This discovery sheds light on the rich…

Unveiling the Hidden Riches: Discovering the Treasure Trove of a Notorious Pirate – Who Was the Pirate? Where Was the Treasure Found? What Historical Insights Does It Reveal? And What Challenges Await Those Who Seek to Uncover Its Secrets?

A group of divers said on May 7 that they had found the treasure of the infamous Scottish pirate William Kidd off the coast of Madagascar. Diver Barry Clifford and his team from Massachusetts – USA went to Madagascar and…

Excavation Update: Archaeologists Unearth Massive Cache of Unopened Sarcophagi Dating Back 2,500 Years at Saqqara – What Secrets Do These Ancient Tombs Hold? How Will They Shed Light on Ancient Egyptian Burial Practices? What Mysteries Await Inside? And Why Were They Buried Untouched for Millennia?

Egypt has unearthed another trove of ancient coffins in the vast Saqqara necropolis south of Cairo, announcing the discovery of more than 80 sarcophagi. The Tourism and Antiquities Ministry said in a statement that archaeologists had found the collection of colourful, sealed caskets which were…

End of content

No more pages to load