Introduction

The Amarna period (1347 – 1336 BC) was undoubtedly one of the most unique stages in the history of ancient Egypt. The establishment of the Egyptian capital in a totally virgin territory so far, the artistic revolution in the representations of the pharaoh and his family or the changes introduced in the religious world are some of its most important aspects, but not the only ones.

At the end of the 19th century, a peasant woman discovered by chance the so-called Amarna letters, an archive of contemporary documentation to Amenhotep III (1390 – 1352 BC) and Amenhotep IV / Akhenaten (1352-1336 BC) which has become a great treasure of Egyptology.

In this article we are going to try to summarize what the Amarna letters are, what are the themes that their contents deal with or who are the protagonists who speak to us through them.

What are the Amarna Letters?

Around 1347 BC, in his fifth year as sovereign, Amenhotep IV took a radical turn in his reign by changing his name: he was renamed Akhenaten, which literally means ” one who effectively acts for the good of Aten.”

As part of his revolutionary program, the pharaoh moved the capital of the country to a newly created city in a territory never before inhabited: Tell el-Amarna, originally known as Akhetaten, that is, “horizon of Aten”.

At the same time that thousands of people of different conditions moved to live in Amarna, so did the main officials of the kingdom.

With them traveled the documents that would make up the great Tell el-Amarna archive, located in the so-called House of Correspondence of the Pharaoh.

The missives in the Amarna archive are engraved in cuneiform script and in Akkadian, one of the lingua francas for international relations.

The language used in these clay tablets flees from formalities and goes into directly analyzing issues such as the political situation of the kingdoms, marital alliances, disputes and diplomatic cordialities, war reports…

To reach their destination, they were transported by officials who sometimes had to walk hundreds of kilometers to fulfill their mission.

The discovery of the first letters occurred fortuitously during the illegal excavations that Farag Ismain was carrying out in the area in mid-1887.

Shortly after, the excavations of the Egyptologist William Flinders Petrie began to bring to light new custom letters that the remains of the Pharaoh’s House of Correspondence were identified.

We do not know the approximate number of tablets that it must have housed at the peak of the Amarnian period, but at present we conserve about four hundred which are distributed between the British Museum in London, the Old Museum in Berlin and the Museum in Cairo.

Contents of the Amarna letters

The fundamental factor that makes the Amarna archive so valuable is its uniqueness, since it is the only set of diplomatic texts that the Nile civilization has bequeathed to us.

The letters are an exceptional testimony of Egypt’s international relations with the great powers of the Middle East from the end of the reign of Amenhotep III, the entire reign of Akhenaten and the beginning of that of Tutankhamun (1336 – 1327 BC).

The scribes who were in charge of writing the Amarna letters that the ambassadors would later carry also played a fundamental role, often working as translators.

After all, the accuracy of the translation depended on whether the message arrived exactly as it should. An incorrect intonation or a badly translated word could generate a misunderstanding that could lead to an international conflict.

Example of five Amarna letters exhibited in the British Museum in London

What are the Amarna letters about?

Within the Amarna letters, one of the requests that is repeated the most, on the part of the pharaoh, is that of princesses and servants of foreign courts.

This marriage circuit was not reciprocal, since the Egyptian sovereign showed his desire to marry Asian princesses while making it clear that he was not willing to send any of his daughters out of the kingdom.

However, that does not mean that they did not achieve anything. In the case of Babylon, for example, we know that they sent princesses to Egypt in exchange for large amounts of gold .

Let’s see to finalize some specific cases. One of the Amarna letters indicates that Amenhotep III requested the hand of Princess Kiluhepa of Mittani. The princess then moved to Egypt accompanied by more than three hundred servants.

Another letter specifies the long list of goods that the Mittanian king Tushratta (approx. 1375-1350 BC) contributed as a dowry to his daughter Taduhepa , who eventually traveled with 300 men and women for her personal service.

In another, King Burna-Buriash II of Babylon(approx. 1359 – 1333 BC) complained about the little pomp with which he had transferred his daughter to the country of the Nile, as if she were anybody.

Also angry, Kadashman-Enlil I of Babylon (1374 – 1360 BC) showed his indignation to Amenhotep III for not wanting to give one of his daughters as a wife.

In conclusion, the Amarna letters allow us to peek through a knowledge gap into a world of kings, princesses, courts and entanglements that we could not have accessed through archeology or the texts that were represented in stelae, temples, tombs or palaces.

For all these reasons, this archive is one of the most relevant sources of knowledge that we have when it comes to reconstructing the relationship of political forces existing in Egypt and the Middle East in the 14th century BC in particular and in the Egyptian New Kingdom in general.

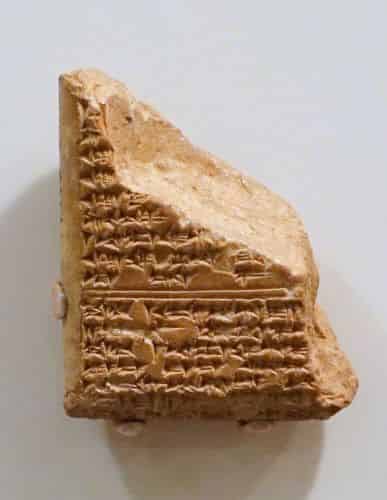

Fragment of one of the letters between King Tushratta of Mittani and the Egyptian pharaoh

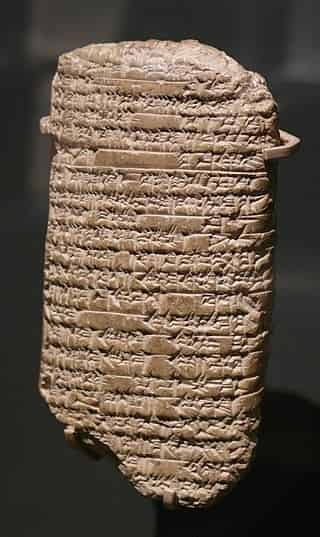

Tablet containing a letter between King Burna-Buriash II of Babylon and the Egyptian pharaoh

News

Unveiling the Ingenious Engineering of the Inca Civilization: The Mystery of the Drill Holes at the Door of the Moon Temple in Qorikancha – How Were They Made? What Tools Were Used? What Secrets Do They Hold About Inca Technology? And What Does Their Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of Ancient Construction Methods?

In the heart of Cusco, Peru, nestled within the ancient Qorikancha complex, lies a fascinating testament to the advanced engineering prowess of the Inca civilization. Here, archaeologists have uncovered meticulously angled drill holes adorning the stone walls of the Door…

Unveiling the Sun Stone: Aztec Relic from the Reign of Moctezuma II (1502-1520) – What Secrets Does It Hold? How Was It Used? What Symbolism Does It Carry? And What Does Its Discovery Reveal About Aztec Culture?

In the heart of Mexico City, amidst the bustling Plaza Mayor, lies a silent sentinel of ancient wisdom and artistry – the Sun Stone. This awe-inspiring artifact, dating back to the reign of Moctezuma II in the early 16th century,…

Uncovering the Past: Rare 1,000-Year-Old Copper Arrowhead Found – Who Crafted It? What Was Its Purpose? How Did It End Up Preserved for So Long? And What Insights Does It Offer into Ancient Societies?

In the realm of archaeology, every discovery has the potential to shed light on our shared human history. Recently, a remarkable find has captured the attention of researchers and enthusiasts alike – a rare, 1,000-year-old copper arrowhead. This ancient artifact…

Unveiling History: The Discovery of an Old Sword in Wisła, Poland – What Secrets Does It Hold? Who Owned It? How Did It End Up There? And What Does Its Discovery Mean for Our Understanding of the Past?

In a remarkable archaeological find that has captured the imagination of historians and enthusiasts alike, an old sword dating back to the 9th-10th century AD has been unearthed in Wisła (Vistula River) near Włocławek, Poland. This discovery sheds light on the rich…

Unveiling the Hidden Riches: Discovering the Treasure Trove of a Notorious Pirate – Who Was the Pirate? Where Was the Treasure Found? What Historical Insights Does It Reveal? And What Challenges Await Those Who Seek to Uncover Its Secrets?

A group of divers said on May 7 that they had found the treasure of the infamous Scottish pirate William Kidd off the coast of Madagascar. Diver Barry Clifford and his team from Massachusetts – USA went to Madagascar and…

Excavation Update: Archaeologists Unearth Massive Cache of Unopened Sarcophagi Dating Back 2,500 Years at Saqqara – What Secrets Do These Ancient Tombs Hold? How Will They Shed Light on Ancient Egyptian Burial Practices? What Mysteries Await Inside? And Why Were They Buried Untouched for Millennia?

Egypt has unearthed another trove of ancient coffins in the vast Saqqara necropolis south of Cairo, announcing the discovery of more than 80 sarcophagi. The Tourism and Antiquities Ministry said in a statement that archaeologists had found the collection of colourful, sealed caskets which were…

End of content

No more pages to load