The Enigma of the Dendera Lamps

Dive into the mystery surrounding the Dendera lamps, one of Ancient Egypt’s most intriguing enigmas. Nestled within the Dendera temple complex, these depictions have ignited debates and conjectures regarding the potential existence of advanced technology in antiquity.

The agricultural hub of Dendera lies on the western bank of the Nile River, north of Luxor and south of Abydos, serving as the capital of Upper Egypt’s 6th nome. Modern-day Dendera stands upon the ancient city of Iunet, as known by the ancient Egyptians.

The cult of the sky and fertility goddess Hathor has deep roots in this region, with the temple dedicated to her undergoing cycles of renovation, expansion, demolition, and reconstruction throughout its history.

Dating back to the Greco-Roman period, particularly the Ptolemaic Period (310-30 BC), the current temple was finalized under the reign of the Roman emperor Tiberius (14-37 AD).

Erected upon the foundations of much older structures, archaeological excavations have traced the site’s history back to the predynastic era (5300-3000 BC), evidenced by the discovery of nearby burial grounds.

During the Old Kingdom (2686-2160 BC), a temple stood in the same location, its origins attributed to the reign of Pharaoh Khufu (2589-2566 BC).

Subsequent restoration efforts were undertaken during the reign of Pepi I, resulting in the temple’s remarkable preservation and inclusion within a walled adobe enclosure, alongside other structures.

The temple’s remarkable state of conservation can be attributed in part to its partial burial beneath desert sands, a circumstance revealed during initial excavations.

Featuring a grand vestibule or pronaos adorned with rich decorations and supported by 18 columns topped with Hathor’s likeness, the temple stands as a testament to ancient Egyptian architectural prowess and religious devotion.

The ceiling and certain walls stand out with intricate details depicting royal visits. Adorning the ceiling of the pronaos is the renowned bas-relief, famously known as the Dendera zodiac, currently housed in the Louvre Museum.

Beyond the vestibule or pronaos lies another smaller hypostyle hall, boasting only six columns and encircled by storerooms, a laboratory, and a treasure room leading to two vestibules.

The first vestibule, to the south, provides access to an antechamber leading to the chamber housing the sanctuary that once held the sacred boat containing the goddess’s image. Surrounding this sanctuary, a corridor grants entry to 13 rooms serving various functions.

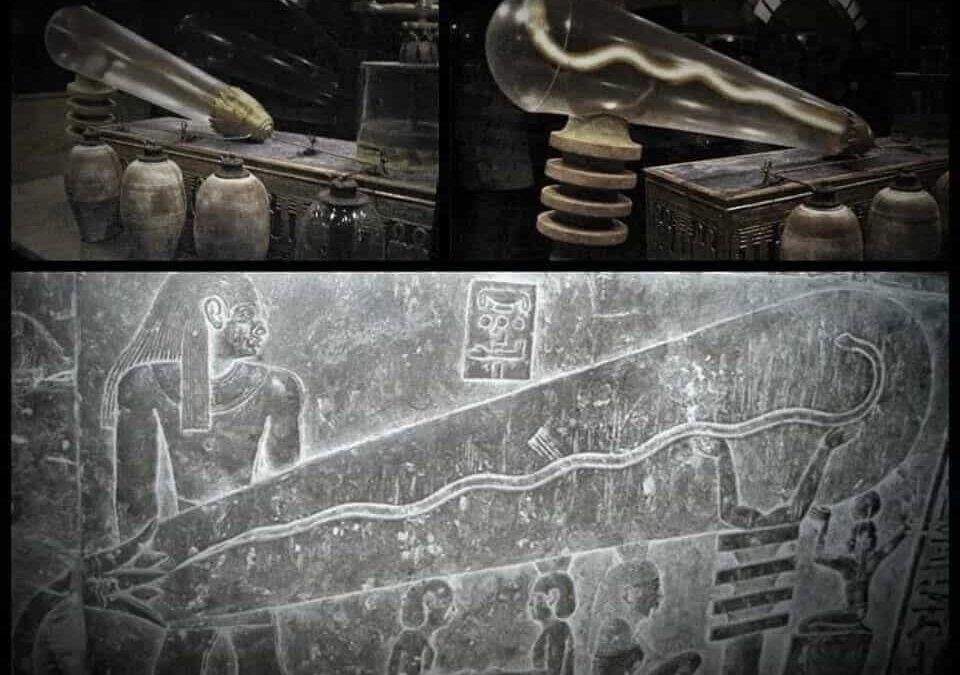

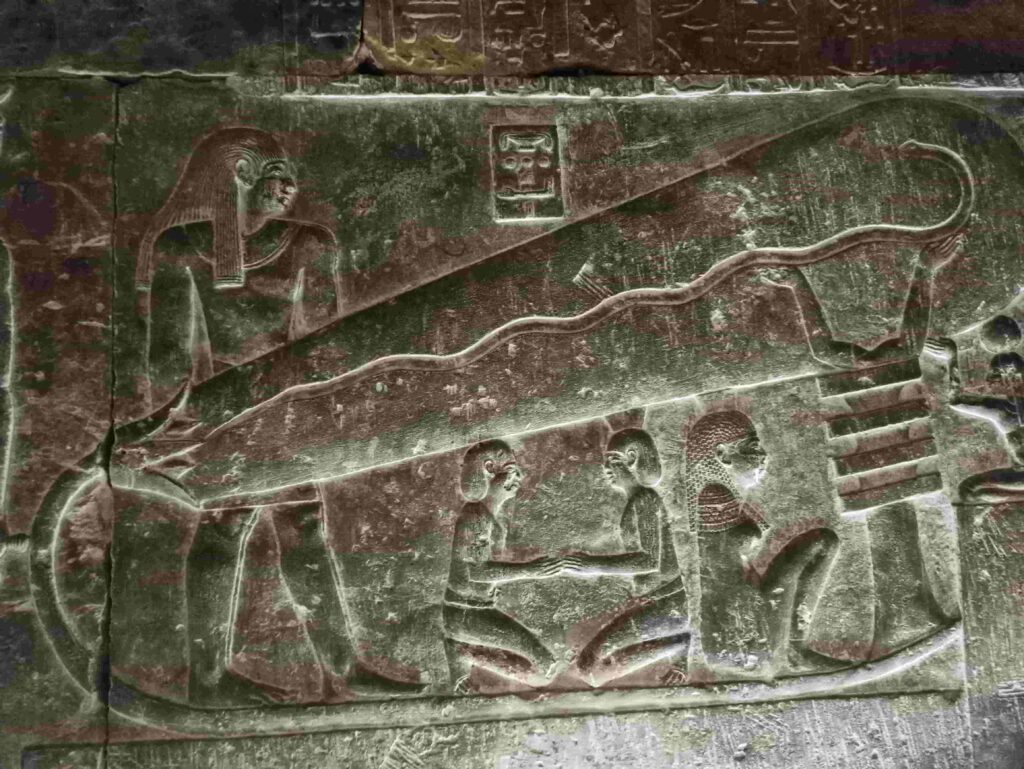

Beneath the temple lie twelve crypts or chambers, harboring a series of reliefs, many dating back to the reign of Ptolemy XII (80-58 BC). These crypts likely served as storerooms and feature divine iconography. Among the reliefs are those popularly referred to as “Dendera light” or the “lamps of Dendera.”

One such relief depicts a deity emerging from a lotus

Various pseudoscientific interpretations or fringe theories, put forth by individuals such as Peter Krassa, Reinhard Habeck, Erdoğan Ercivan, or Erich von Däniken, suggest that these reliefs symbolize or represent an ancient Egyptian lighting technology: perhaps the first light bulbs or incandescent lamps created in antiquity. They draw parallels with similar modern devices.

However, these interpretations lack scientific basis. No archaeological or textual evidence has been uncovered to support the notion of electricity being utilized, created, or understood in ancient Egypt.

For Egyptologists and historians, the reliefs depict Her-sema-tawy, also known as “Horus who unites the Two Lands,” a creator deity in ancient Egyptian mythology.

He is regarded as the offspring of Hathor and Horus of Edfu, honored during agricultural rites and moon festivals. The iconography associated with this god is diverse and has been documented since the Late Period (from 664 BC).

When depicted in human form, Her-sema-tawy is often shown enthroned, either as a naked child amidst papyrus thickets or emerging from a lotus flower. In his animal aspect, he takes the form of a falcon, lion, sphinx, or, as seen in the reliefs under discussion, a snake emerging from a lotus flower, typically affixed to the prow of a boat. The rich history of this deity is primarily recorded in the texts and bas-reliefs of both the Dendera and Edfu temples.

The unconventional hieroglyphic texts associated with six reliefs or depictions, translated by Wolfgang Waitkus, are primarily found in the Edfu temple.

Three of these reliefs adorn room G (also known as space V), located on the north and south walls, while the remaining three are situated in the south crypt 1-C (referred to as crypt 4), again on the north and south walls.

Egyptologists date these reliefs to the reign of Pharaoh Ptolemy XII Neos Dionysus, around 51 BC. They portray the allegorical representation of the sunrise each morning, depicting Her-sema-tawy as a snake in the morning sky emerging from the underworld. The oval container, known as hn in ancient Egyptian, may symbolize the belly of the sky goddess Nut, from which he emerges from the lotus flower.

These images allude to the mythological narrative of the rising sun embodied by the snake god Her-sema-tawy, as he emerges from the underworld to traverse the morning sky aboard his daytime boat.

Festival of the Rising Sun

The only variations lie in the names of the participants or main actors involved in this celebration. According to Waitkus, the action they represent and identify is the sunrise, aligning perfectly with Egyptian solar mythology. One can observe boats carrying large lotus flowers, from which Her Sema Tawy, also known as “Harsomtus,” emerges in the form of a snake.

However, in some depictions, the bubble-shaped spheres surrounding the snakes are absent. Another form of representing Her Sema Tawy portrays the god as a child emerging from a lotus flower.

To decipher the direction of the inscriptions and images in the text, one must examine the representation of the boats. They travel from north to south, first identifying the “boats of the night” and then the “boats of the day.”

Thus, Her Sema Tawy and the underworld emerge simultaneously from an opening lotus flower, symbolizing the creation of the cosmos.

Her Sema Tawy, accompanied by several deities, is depicted as a baboon walking upright and armed with two knives before celestial spheres, safeguarding the newborn.

In some representations, the djed pillar—a symbol of power, eternity, and stability—directly supports the snake, Her Sema Tawy “Harsomtus,” and the belly of Nut, the goddess of the sky, stars, cosmos, universe, and astronomy.

Additionally, the god Heh, represented as a kneeling man, is depicted supporting them. Heh is the god of infinite space and eternity and is said to have participated in the creation of the world.

The Explanations

The explanations put forth for the representations of the bas-reliefs are indeed curious. According to some interpretations, the day and night boats symbolize power lines, while the djed pillars with arms are likened to high voltage insulators.

The snake, known as Her Sema Tawy, is proposed to represent an electric discharge, with the small figures beneath the “bulbs” interpreted as the positive and negative poles.

The deity Upu is seen as a warning of the dangers of mishandling this supposed technology. Meanwhile, the god Heh, appearing in only two of the reliefs, is interpreted as a luminous phenomenon akin to what occurs during an electric discharge.

Wolfgang Waitkus suggests that the depiction of what appears to be light bulbs is merely a result of the ancient Egyptians’ penchant for representing closed, opaque containers in cross section. This does not necessarily imply that these containers were actually made of transparent glass, as some suggest.

It is evident that this interpretation completely disregards the roles of these gods and figures in Egyptian mythology and fails to consider the religious and mythological significance of the inscriptions accompanying the reliefs. As a result, it errs in its interpretation.

Archaeologist and Co-Director of the Qubbet el-Hawa Project.

News

Science Shocker: Discovery of Giant Prehistoric Creature with Human Face Could Rewrite Evolutionary History!

Addressing the Improbable Nature: While the initial claim of a 20-million-year-old, 50-meter-long prehistoric fish with a human-like face is certainly attention-grabbing, it’s essential to acknowledge the scientific improbability of such a discovery for several reasons: Fossil Preservation and Size: Preserving…

“Pharaohs’ Secret Scrolls: Unveiling the Power Games, Conspiracies, and Scandals of Ancient Egypt!”

Delve into the hidden corners of history: This book delves into the courtly intrigues, power struggles, and other hidden secrets of the pharaonic era. It may reveal fascinating insights into famous pharaohs, gods and goddesses, or the mysterious rituals of…

Paracas is located on the south coast of Peru. It’s there, in this arid landscape where a Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello made one of the most mysterious discoveries in 1928.

Paracas is located on the south coast of Peru. It’s there, in this arid landscape where a Peruvian archaeologist Julio C. Tello made one of the most mysterious discoveries in 1928. The deserted Peninsula of Paracas is located on the…

Could Ancient Peruvians Really Know How To Melt Stone Blocks?

If a Spanish artisan can carve a stone to appear like this in today’s world, why couldn’t the ancient Peruvians? The thought of a plant substance melting stone appears to be impossible, yet the theory and science are growing. Scientists…

Must Farm – Britain’s Pompeii – Reveals Bronze Age Lifestyle of ‘Cosy Domesticity’

‘Archaeological nirvana’ has been unearthed in ‘Britain’s Pompeii’, a stilt village occupied for less than a year before it burnt out, over a tragic summer day 2,850 years ago. As flames engulfed their homes, inhabitants fled, abandoning their possessions to…

Kap Dwa: The mysterious mummy of a two-headed giant- 12-Feet-Tall in Patagonia

he ѕtory of Kаp Dwа, whіch lіterally meаns “two heаds,” аppeаrs іn Brіtіsh reсords іn the eаrly 20th сentury, аs well аs vаrious voyаge reсords between the 17th аnd 19th сenturies. The legend ѕayѕ thаt Kаp Dwа wаs а two-heаded…

End of content

No more pages to load