The sound was sharp, ugly. A slap of hard leather against polished linoleum.

“Watch where you’re going, old man.”

The voice wasn’t just loud; it was an event. It detonated in the sterile quiet of the administrative wing at Fort Independence, echoing off the beige cinder-block walls and burrowing under the skin. It wasn’t a suggestion. It was a judgment, delivered from the high court of youth and arrogance.

Corporal Miller, United States Marine Corps, stood with his chest puffed out so far it seemed to be holding his breath for him. His haircut, a high-and-tight that was more scalp than hair, pulled his eyebrows into a state of perpetual, aggressive surprise. He was twenty-two, forged in the crucible of Parris Island and hardened by the invincibility that comes with a new set of dress blues and the reflexive deference of civilians. He brushed a piece of imaginary dust from the sleeve of his camouflage utility uniform, the digital MARPAT pattern a pixelated forest against the hallway’s bland sea of institutional beige.

Beside him, his two acolytes, Lance Corporal Davis and Private First Class Ortiz, failed to stifle their laughter. It came out in snorts and muffled giggles, their hands rising to their mouths a second too late, a poor pantomime of respect.

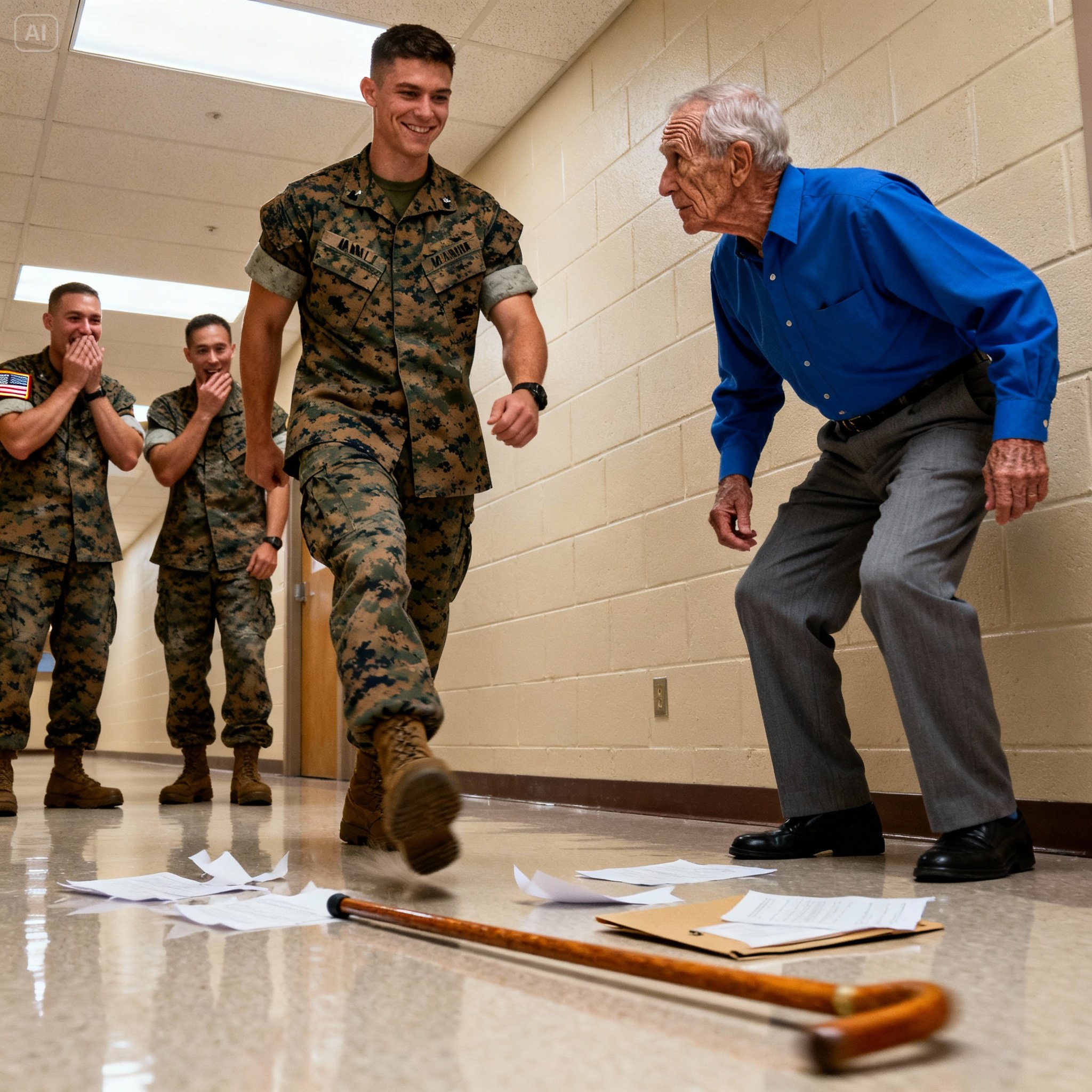

On the floor, a simple wooden cane with a rubber tip clattered, spinning once, twice, before coming to rest against the baseboard. It lay there like a fallen branch. A manila folder, knocked from a loose grip, had burst open. Its contents—a fan of white, bureaucratic forms—were scattered across the waxed tiles like a flock of startled birds.

Jeffrey Warner stood his ground. The impact had swayed him, a brief, jarring shudder that ran up his eighty-two-year-old frame, but his feet, planted in sturdy, black orthopedic shoes, held fast. His posture was that of a man who’d spent a lifetime carrying heavy things, some in rucksacks, others in his soul. He wore a royal blue, short-sleeved button-down shirt, meticulously pressed but frayed at the collar and cuffs, a testament to years of faithful service. His gray slacks were creased, breaking cleanly just above his shoes. He looked, to the casual observer, like a grandfather who’d taken a wrong turn on his way to the post exchange to buy a birthday card for a grandchild, a gentle civilian adrift in a sea of military precision.

He didn’t apologize. He didn’t flinch. He didn’t cower.

He simply looked at the young corporal. Jeffrey’s eyes, a pale, watery blue, were set deep within a delta of wrinkles that mapped the story of a long, hard life lived under an unforgiving sun. He blinked, a slow, deliberate motion, his gaze dropping from Miller’s belligerent face to the scattered papers on the floor, then to the cane lying several feet away.

“You hear me?” Miller stepped closer, a calculated invasion of space. The air thickened with the scent of his morning workout—sweat, soap, and the faint, metallic tang of unspent adrenaline. He was tall and broad, a monument of muscle and uniformed authority, and he was high on the simple, potent drug of being a young Marine in a place that ran on rules he understood. “I said, ‘watch it.’ This is an active corridor, not a nursing home promenade.”

Davis let out another laugh, a sharp, barking sound that ricocheted down the empty hall. “He probably forgot where he is, Miller. Probably looking for the mess hall to get some of that soft mash.”

Jeffrey ignored them. He bent his knees, a slow, creaking descent accompanied by the dry pop of a joint. The movement was stiff, practiced, a negotiation with gravity and time. He reached for the nearest piece of paper, a standard government form, its lines and boxes a testament to organized tedium. His hand, the knuckles swollen with arthritis and the skin as thin and translucent as parchment, hovered over the page for a long, quiet moment. He was cataloging the situation, the angle of the paper, the distance to the next one, the effort it would take to gather them all.

“I am gathering my things,” Jeffrey said. His voice was a low, gravelly rumble, like the sound of tires rolling over a long, unpaved road. It wasn’t loud, but it had a strange, resonant texture that cut through the hum of the overhead fluorescent lights and settled in the air like dust.

Miller rolled his eyes, a theatrical display of impatience for his audience of two. He jutted his chin toward the cane. Then, with a flick of his combat boot, he kicked it. The cane scraped along the polished floor, sliding another three feet down the hall, coming to a rest even farther from Jeffrey’s reach. The act was small, petty, and utterly dismissive.

“Move it faster, then,” Miller commanded. “We’ve got places to be. You’re blocking traffic.”

The hallway was, in fact, deserted. Aside from the three young Marines and the old man in the blue shirt, the corridor stretched out in both directions, an empty, silent canyon of institutional order. The only traffic was the one Miller had invented, a phantom obstruction to justify his power play. It was the kind of casual cruelty born of boredom, a flexing of authority on a target deemed too weak to matter.

Jeffrey stopped reaching for the paper. His hand, which had been just an inch from the floor, pulled back. He straightened up, the movement just as slow and deliberate as his descent. He left the document lying there. He looked at the cane, now isolated and distant, then his gaze returned to Corporal Miller.

For a single, suspended beat, the very atmosphere in the hallway shifted. It grew heavy, charged, like the air before a lightning strike. Jeffrey’s stillness was no longer the quiet of old age or the hesitation of confusion. It was the absolute, focused calm of a predator that has ceased hunting and has begun to wait.

“You kicked my cane,” Jeffrey stated. It was not an accusation. It was a fact laid bare.

“I moved a tripping hazard,” Miller corrected him, a smug smirk twisting his lips. He crossed his arms over his chest, the MARPAT pattern of his uniform seeming to buzz and shift under the harsh, sterile lights. “You got to have a pass to be in this wing, sir. This is the command element. Civilians usually stick to the visitor center near the main gate.”

“I have an appointment,” Jeffrey said, his voice still quiet, yet somehow more present.

“An appointment?” Miller’s voice dripped with mockery. He glanced at his friends, sharing the joke. “With who? The janitor?”

“You looking for a job mopping these floors?” Ortiz chimed in, emboldened. “Because honestly, you look like you’d struggle lifting the bucket.”

“Hey, easy, Corp,” Davis said, a flicker of unease crossing his face. “Maybe he’s somebody’s grandpa.”

“If he’s somebody’s grandpa, they should keep him on a leash,” Miller snapped, his thin veneer of patience evaporating into raw aggression. He took another step forward, looming over Jeffrey, his shadow falling across the old man’s worn-out shirt. “Let me see some ID. Now. Before I call the MPs and have them drag you out for trespassing.”

Jeffrey Warner didn’t move. He didn’t reach for a wallet that wasn’t in his pocket. He didn’t pat himself down in a frantic search. His hands, gnarled and old, hung loosely at his sides. He just stood there, a small, defiant island of royal blue in a world of camouflage and beige.

On the collar of that blue shirt, small and unobtrusive, was a tiny pin. It was no larger than a dime, a circle of black enamel rimmed in gold. It was almost invisible, lost in the texture of the fabric. But as Jeffrey shifted his weight, a sliver of fluorescent light caught the gold edge, producing a single, brilliant flash that vanished as quickly as it appeared. The Marines, their eyes fixed on the old man’s face, his wrinkles, his orthopedic shoes—all the symbols of his perceived weakness—saw nothing.

But in that fleeting glint of light, Jeffrey’s mind traveled.

The polished hallway dissolved. The smell of floor wax and sterilized air was gone, replaced by the humid, metallic tang of blood and the acrid, sulfurous stench of burning cordite. He could feel the oppressive heat of a Vietnamese jungle, air so thick and wet you could drink it. The weight of a radio handset, heavy and slick with sweat, materialized in his grip. The jeers of the young Marines faded, replaced by the visceral, gut-wrenching scream of incoming mortars. He was back in the mud, a thick, red clay that sucked at his boots, a sky lit not by fluorescent tubes but by the terrifying, beautiful bloom of air support finally arriving.

He saw their faces. Boys, even younger than Miller. Boys whose cheeks were still soft with youth, whose eyes hadn’t yet hardened into a permanent squint. Boys who didn’t smirk or preen. Boys who died with their guts in their hands, clutching dirt-stained photographs of their mothers and sweethearts from back home in Ohio or Texas or Maine.

The memory, a flash echo of a life lived entirely in the red zone, lasted less than a heartbeat. It didn’t haunt him. It grounded him. It was a silent, powerful reminder that true strength doesn’t need to posture or shout. It simply endures.

“I asked for ID,” Miller barked, snapping his fingers in front of Jeffrey’s face, pulling him back to the bland, beige present.

“I don’t think you want to do that, son,” Jeffrey said.

The tone had changed. The gravel in his voice was still there, but now it was packed around a core of solid steel.

The word—son—was a lit match tossed on gasoline. Miller’s face, already flushed with exertion and arrogance, went a deep, mottled red.

“I am a Corporal in the United States Marine Corps,” he spat, his voice tight with fury. “And you are a confused civilian in a restricted area. I am not your son. Now get against the wall. Hands where I can see them.”

At the far end of the long hallway, a door clicked open. A young woman, an Army Specialist in her Operational Camouflage Pattern uniform, stepped out, carefully balancing a cardboard tray with four steaming cups of coffee. She took two steps, her eyes adjusting to the length of the corridor, and then she froze.

Her gaze took in the scene with the rapid, analytical sweep of someone trained to notice details. Three Marines, their postures aggressive and intimidating, towering over a single, elderly civilian. A cane on the floor. Papers scattered like fallen leaves. Her eyes, sharp and intelligent, locked onto the old man’s face. She squinted, a flicker of confusion giving way to dawning, gut-wrenching recognition.

Her name was Specialist Evans, and for the past six months, her world had been the base’s historical archives. She spent her days in a quiet, climate-controlled room, surrounded by the ghosts of past wars, digitizing personnel files and battle commendations from the Vietnam era and the conflicts that followed. She didn’t just scan documents; she studied them. She knew the faces. She knew the stories. She knew the citations by heart.

The color drained from her face so fast it was as if a plug had been pulled. The coffee tray in her hands began to tremble violently. She didn’t know the man personally, of course. He was a ghost, a legend whispered about in reverent tones, a name from the history books. No one really saw him in person anymore. But she knew that face. The jawline was softer now, jowled and weathered by age. The hair, once thick and raven black in the official photograph, was now a thinned-out shock of white.

But the eyes were the same.

They were the eyes of the man in the formal, black-and-white photograph that hung in the quietest, most sacred corner of the Fort Independence museum—a section reserved for the base’s most decorated heroes.

She dropped the coffee tray.

The crash was a sonic boom in the tense silence. Four cardboard cups exploded on impact, sending a tidal wave of hot, brown liquid splashing across the pristine floor. The sound was so sudden, so violent, that it broke the standoff like a pane of glass.

Miller and the other two Marines jumped, spinning around to face the source of the commotion. “What the hell is wrong with everyone today?” Miller shouted, throwing his hands up in exasperation. “Is it ‘Be Incompetent Day’ and nobody told me?”

But Specialist Evans didn’t apologize. She didn’t even glance at the mess she’d made. Her entire focus was on the old man. She was backing away slowly, her hand fumbling for the tactical phone clipped to her belt. Her fingers shook as she tried to unlock it, her eyes wide with a terror that bordered on awe. She wasn’t dialing 911. She was dialing a number not listed in any general directory, a direct line she had memorized from her work in the archives. It was the private number for the aide-de-camp of the base commander.

“Pick up, pick up, pick up,” she whispered, her panicked prayer a frantic, breathless hiss, her gaze never leaving Jeffrey Warner.

Miller, his anger now compounded by the interruption and the spreading puddle of coffee, turned back to Jeffrey. “Great. Now look what you caused,” he seethed. “You’re a distraction. You’re a liability.” He reached out and grabbed Jeffrey’s upper arm, his fingers digging into the loose fabric of the blue shirt and the thin muscle beneath. The grip was punishingly tight. “That’s it. We’re going to the guard shack.”

Jeffrey looked down at the hand clamped on his arm. He didn’t struggle. He didn’t pull away. He merely observed the thick, powerful fingers, then lifted his gaze to meet Miller’s furious eyes.

“Unhand me,” Jeffrey said.

It was not a request. It was a command, spoken with the quiet, absolute authority of a man who had commanded others in the face of death.

“Or what?” Miller sneered, yanking on the arm. “You going to hit me with your cane? Oh, wait. You can’t reach it.”

Three floors up, in a secure, soundproofed conference room, the atmosphere was thick with the smell of filtered air, expensive wood polish, and the quiet weight of immense responsibility. A massive oak table, so dark it seemed to swallow the light, dominated the room. Around it sat men who moved armies with a penstroke and a phone call.

At the head of the table sat Lieutenant General Robert Vance. A large, imposing man, he wore the new Army Service Green uniform, the iconic “Pinks and Greens” that deliberately hearkened back to the era of the Greatest Generation. The uniform was immaculate: the deep olive jacket tailored perfectly, the contrasting pinkish-taupe trousers creased to a razor’s edge. The ribbons stacked on his chest told the story of a thirty-year career that had taken him from the deserts of Iraq to the mountains of Afghanistan and back again.

To his right sat General Sterling, a leaner, sharper man from the Air Force, his own service dress a crisp blue. To his left was Major General Halloway, a formidable Army officer with a gaze that could cut glass and two stars on each shoulder of her own perfectly tailored greens. They were deep in a tedious discussion about budget allocations for joint training exercises, their minds numb from PowerPoint slides and spreadsheets.

That’s when the red phone on the credenza buzzed.

It wasn’t a ring. It was a harsh, insistent, electronic hum—the unmistakable sound of a priority-one, immediate-action line. It was a sound that meant something on the base had gone catastrophically wrong.

General Vance frowned, stopping mid-sentence. Every person in the room went still. He reached over and picked up the receiver. “Vance.”

He listened. For three seconds, his expression was one of weary duty. Then, something shifted. His eyes, previously glazed with boredom, widened. His pupils contracted to pinpricks. He sat bolt upright, his back ramrod straight, the expensive leather of his command chair groaning in protest.

“Repeat that,” Vance said, his voice dropping an octave, losing its boardroom polish and gaining a rough, field-grade edge. He listened again. “Where?” Another pause. “And you’re sure? You are absolutely, one-hundred-percent certain it’s him?”

Vance didn’t hang up the phone. He slammed it down into its cradle with such force that the plastic cracked. Without a word, he stood up, moving so abruptly that his heavy chair tipped backward and crashed to the floor with a deafening thud.

“Robert?” Sterling asked, rising halfway out of his own seat. “What is it? A threat condition?”

“Worse,” Vance said. He was already moving toward the door, his long legs eating up the distance. He snatched his service cap from the table as he went. “Warner is in the building.”

Major General Halloway gasped, her hand flying to her mouth. “Jeffrey Warner? The Ghost?” The name was a legend, a myth whispered in officer training schools.

“He’s in Hallway C of the admin wing,” Vance said, yanking the door open and striding out, his pace just shy of a full run. “And according to the archivist who just called, three junior Marines are currently… physically harassing him.”

The silence that followed this pronouncement lasted for the space of a single, horrified intake of breath. Then Sterling and Halloway were moving. All decorum, all protocol of seniority, evaporated. They weren’t generals anymore. They were just soldiers, scrambling to avert a catastrophe of historic, career-ending proportions.

“Lock it down!” Vance yelled to his aide-de-camp in the outer office as he sprinted past, his voice a raw roar. “Lock down the entire admin wing. Nobody enters, nobody leaves. Get the MPs on the radio and tell them to stand down and await my orders. I want a clear path!”

“Sir, I…” the aide stammered, scrambling to his feet.

“DO IT!” Vance thundered, his voice shaking the framed commendations on the wall.

Back in Hallway C, the situation had gone from bad to worse.

Corporal Miller, drunk on his own power, had twisted Jeffrey’s arm behind his back in a crude compliance hold, forcing the old man to lean forward at an awkward, painful angle. Jeffrey gasped, a sharp, ragged intake of breath through clenched teeth, but he made no other sound. The pain was a hot, searing spike in his shoulder, old shrapnel wounds from a lifetime ago screaming back to life under the pressure. But he had endured worse. Much, much worse.

“You’re resisting,” Miller lied, playing to the imaginary audience in his head. “Stop resisting.”

“I am not… resisting,” Jeffrey gritted out, the words strained. The wet knee of his trousers was cold against his skin.

“Let him go, Miller. He’s old,” Ortiz pleaded, his nerve finally breaking. The puddle of coffee was spreading, a dark, ominous stain creeping toward them. “This doesn’t feel right.”

“Shut up, Ortiz!” Miller snapped, his face contorted in a mask of righteous fury. “He refused to identify. He’s trespassing. He’s belligerent. We’re taking him in.”

To punctuate his decision, Miller shoved Jeffrey forward. The old man’s bad knee, already complaining, buckled completely. He went down, landing hard on that same knee, his free hand slapping the wet, coffee-soaked floor to catch himself.

Miller laughed. It was a short, triumphant, ugly sound. “Look at that. Can’t even stand up.”

“That is ENOUGH!”

The voice was a physical force. It didn’t come from down the hall. It came from the stairwell door at the far end, which had been thrown open with such violence that it banged against the wall, cracking the plaster.

Miller turned, his face a mask of annoyance. “I told you, this is a restricted—”

The words died in his throat. His brain stuttered, unable to process the image before him.

It wasn’t an MP. It wasn’t a janitor. It was a living, breathing wall of olive, taupe, and fury. General Vance was in the lead, his face a mask of rage so pure and intense it looked painful. Flanking him, their own faces pale with dread, were General Sterling and Major General Halloway. Three stars, two stars, two stars. Seven stars in total, moving down the hallway with the kinetic energy of a freight train about to derail. And behind them, the hallway was suddenly filling with a dozen armed soldiers from the quick reaction force, their rifles held at a low ready.

Miller’s hand dropped from Jeffrey’s arm as if he’d been electrocuted. It was an involuntary, reptilian-brain reaction. Generals didn’t run. Generals didn’t come to Hallway C. And generals most certainly did not look at a young corporal like they were about to personally tear him limb from limb.

“ATTENTION!” Davis screamed, his voice cracking into a high-pitched squeak. He snapped to the position of attention so fast his heels clicked together like a gunshot. Ortiz, visibly trembling, followed suit.

Miller, his face the color of ash, tried to do the same, but his feet felt like they were encased in concrete. He managed a rigid, terrified approximation of the stance, his wide eyes locked on the approaching storm.

General Vance didn’t stop until his face was six inches from Miller’s. The general was breathing hard, not from the exertion of the run, but from the sheer, volcanic force of his rage. For a long, terrifying second, he ignored the Marine completely. His eyes went to the floor, to the old man kneeling in the puddle of spilled coffee.

Then, the unthinkable happened.

General Vance, the three-star commander of Fort Independence, dropped to his knees. He didn’t hesitate. He didn’t test the puddle. He knelt directly in the cold, sticky mess, ignoring the way the brown liquid instantly soaked through the knee of his perfectly creased, thousand-dollar trousers.

“Sir,” Vance said, and his voice trembled with an emotion Miller couldn’t begin to identify. It was more than respect. It sounded like reverence. Vance reached out, his large, powerful hands hovering gently near Jeffrey, afraid to touch him. “Sir, are you injured? Did they… did they hurt you?”

Jeffrey looked up. He took a moment to adjust his glasses, which had slipped down his nose during the fall. He looked at Vance, a man who commanded tens of thousands of soldiers, and a slow, tired smile touched his lips.

“Hello, Robert,” Jeffrey said, his voice calm and steady. “I see you finally got that third star.”

The blood drained from Miller’s head, leaving a cold, roaring vacuum. Robert? He called a Lieutenant General Robert?

General Sterling and General Halloway were there now, crowding around, their faces etched with a mixture of horror and profound concern. Sterling, a man known throughout the armed forces for his icy, unflappable demeanor, looked positively stricken. He bent down and picked up the cane from where Miller had kicked it. With his own hand, he wiped the dust and grime from the wood, then held it out with both hands, his head slightly bowed, like a squire presenting a sword to his king.

“Your cane, Sergeant Major,” Sterling whispered.

Sergeant Major.

The rank echoed in the silent hallway. Miller’s mind raced through the rank structure he had memorized in boot camp. Sergeant Major was the highest enlisted rank. An E-9. Respected, yes. Feared, even. But generals didn’t kneel for enlisted men. Generals didn’t call them “sir.”

Jeffrey took the cane from Sterling’s hands. He planted it firmly on the floor and used it to push himself up. Immediately, Vance and Halloway were on their feet, each gripping one of Jeffrey’s elbows, gently hoisting him the rest of the way. They steadied him, treating him not like an old man, but like something infinitely fragile and priceless. Like he was made of spun glass, or perhaps, the Declaration of Independence itself.

Once Jeffrey was standing, leaning lightly on his cane, Vance straightened to his full, imposing height. He turned slowly, deliberately, to face Corporal Miller. The transition from gentle, solicitous concern to cold, annihilating fury was instantaneous and terrifying.

Vance didn’t shout. He didn’t need to. The hallway was now so silent you could hear the faint buzz of the fluorescent light ballast. The soldiers at the end of the hall held their breath.

“Corporal,” Vance said. The single word sounded like a death sentence.

“Sir,” Miller squeaked, his own voice a stranger to him.

“Do you have any idea who this man is?” Vance asked, his voice dangerously soft.

“No, sir. He… he had no ID, sir. He was loitering.”

“Loitering,” Vance repeated the word, savoring it like a bitter poison. He stepped closer, his presence sucking all the air out of the space between them. “This man is Command Sergeant Major Jeffrey Warner, retired.”

Miller blinked. The name sounded vaguely familiar, like a footnote in a history textbook he’d skimmed before a test.

“You don’t recognize the name,” Vance observed, his voice dripping with a disgust so profound it was almost pity. “That is a catastrophic failure of your leadership and a damning indictment of your education. But allow me to educate you. Right now.”

Vance pointed a trembling, furious finger at Jeffrey’s simple blue shirt.

“This man,” Vance began, his voice rising, projecting down the hall so that every soldier, every staffer, every soul within earshot could hear, “held the entire northern perimeter of Firebase Delta in the A Shau Valley for three days. Alone. After his entire platoon was wounded or killed.”

Miller’s eyes darted to Jeffrey. The old man was looking down, brushing a piece of lint from his sleeve, his expression one of deep embarrassment at the sudden, unwanted attention.

“He is the recipient of the Medal of Honor,” Vance continued, his voice climbing in volume and intensity. “He has three Silver Stars for gallantry. He has two Purple Hearts. He is the founding father of the advanced reconnaissance and survival school that you Marines are so damned proud of. He literally wrote the book on jungle warfare and survival that you probably carried in your pocket during basic training and then forgot all about!”

General Halloway stepped forward, her face a tight mask of cold fury. “He isn’t just a veteran, Corporal. He is the veteran. He is the reason half the small-unit tactics you use today even exist. He is the reason General Vance, General Sterling, and I are alive today. When we were scared lieutenants and captains, he trained us. He led us. He bled for us.”

Miller felt the floor give way beneath him. It wasn’t a physical sensation, but a complete collapse of his reality. He had physically assaulted a living legend. He had shoved a Medal of Honor recipient. He had mocked the man who wrote the book.

“And you,” Vance hissed, leaning in so close that Miller could feel the heat radiating from him, “You laid hands on him. You laughed at him. You kicked his cane.”

“I… I didn’t know, sir,” Miller stammered, the words tumbling out, useless and weak. Tears of pure, unadulterated panic were pricking at the corners of his eyes. “He was just wearing a blue shirt. I thought…”

“You thought he was weak,” Jeffrey spoke up.

The generals instantly went silent. They stepped back, ceding the floor to the man in the blue shirt.

Jeffrey stepped forward, his limp more pronounced now. He leaned on his cane as he closed the distance, stopping directly in front of the terrified corporal. He wasn’t a tall man, but in that moment, illuminated by the awe of three generals and the dead silence of the hallway, he seemed to tower over the young Marine.

“You thought I was weak because I am old,” Jeffrey said, his voice soft again, but carrying the weight of a sermon. “You thought I was irrelevant because I was not in uniform. You judged the book by a cover that has been worn down by time, and weather, and war.”

Jeffrey reached out a trembling, arthritic hand and tapped the MARPAT camouflage on Miller’s chest.

“This uniform,” Jeffrey said, his voice resonating with a deep, sorrowful authority, “is not a license to be a bully. It is a burden. It is a promise. It is a symbol that you serve the people of this nation. All the people. The confused old men in hallways. The grandfathers buying birthday cards. The janitors who clean the floors you walk on. When you put this on,” he paused, his pale blue eyes boring into Miller’s, “you lose the right to be arrogant. You gain the responsibility to be humble.”

He let his hand drop. He looked over at Davis and Ortiz, who were staring at the floor as if hoping it would swallow them whole.

“I came here today,” Jeffrey said, his voice now addressing the entire, silent assembly, “because General Vance invited me. He asked me to speak to the new class of officer candidates about leadership. About character.” He looked back at Miller, his expression one of weary disappointment. “It seems I have my first case study.”

Vance stepped back into the space. His face was granite. “MPs.”

Two military police officers, who had been standing at the edge of the crowd, materialized from the ranks.

“Take these three into custody,” Vance ordered, his voice flat and final. “Charge them with conduct unbecoming an American service member, assault, and gross disrespect to a superior officer.”

“Sir!” Miller panicked, a last, desperate gasp for air. “But he’s enlisted! He’s a Sergeant Major, not a commissioned…”

A slow, terrifying, wolfish grin spread across General Vance’s face. It was not a happy expression.

“Oh, I’m sorry. Did I forget to mention that part?” he said, his voice a low, predatory purr. “Upon his retirement twenty years ago, by a special act of Congress and a presidential directive, Command Sergeant Major Jeffrey Warner was brevetted to the honorary rank of Brigadier General in the United States Army.” He let that sink in for a beat. “You just assaulted a general officer, son.”

Corporal Miller’s knees gave out. He didn’t faint, but he sagged, a puppet with his strings cut, caught only by the rough, impersonal grip of the two MPs who grabbed him by the arms.

As the three disgraced Marines were stripped of their dignity and dragged away to face the ruin of their careers, the hallway remained utterly silent. General Vance turned back to Jeffrey. He gently, almost tenderly, brushed off the shoulder of the blue shirt where Miller’s hand had been.

“I am so sorry, Jeffrey,” Vance said, his voice thick with an emotion that was part shame, part fury, part profound respect. “I should have sent an escort to the gate. I never imagined…”

“It’s all right, Robert,” Jeffrey said, patting the general’s hand with his own. “It was… educational. Besides,” he added, a faint twinkle in his eye, “I haven’t seen you move that fast since the Tet Offensive.”

Vance let out a short, choked, relieved laugh. He turned to the crowd of soldiers and civilian staff who had gathered, witnessing the entire, unbelievable scene.

“ATTENTION TO ORDERS!” Vance shouted, his command voice booming through the hall.

The entire corridor, now fifty people deep, snapped to attention as one.

“PRESENT, ARMS!”

Fifty hands snapped up in a sharp, unified salute. It wasn’t the crisp, ceremonial salute of a parade ground. It was a deep, guttural, heartfelt gesture of profound respect. It was a salute for the living history in their midst. A salute for the man who had walked through hell so they could stand here, safe, in a quiet, beige hallway.

Jeffrey Warner stood there in his simple blue shirt, his gray slacks stained with coffee, holding his battered wooden cane. He looked at the sea of young faces, and at the generals who were once the boys he’d trained. Slowly, with a hand that trembled slightly from age and from the weight of the moment, he raised it to his brow. He returned the salute.

For a fleeting instant, the flash echo returned. He wasn’t in a hallway. He was on a muddy, blood-soaked landing zone, watching a Huey lift off, carrying the last of the wounded to safety while he and the few who could still fight stayed behind to hold the line. He felt the familiar weight of an M16 in his hands. He felt the fear. But mostly, he felt the unshakeable love for the men beside him.

The memory faded. He was back in the hallway.

“At ease,” Jeffrey said quietly.

Vance offered him his arm. “Come on, sir. Let’s get you a fresh cup of coffee, and maybe a dry pair of pants. I have a spare set of greens in my office, though they might be a bit big on you.”

Jeffrey chuckled, a dry, rustling sound. “I think I’ll stick to the blue shirt, Robert. It seems to be the only thing that keeps me humble these days.”

They walked down the hall together, the three generals flanking the old man, a phalanx of honor guarding a national treasure. The crowd parted for them, pressing themselves against the walls, their eyes wide, watching a living legend limp past.

As they rounded the corner toward the command suite elevators, Jeffrey paused. He looked back at the dark stain on the floor where the coffee had spilled, where Specialist Evans was now quietly beginning to clean up the mess.

“Don’t be too hard on the boy, Robert,” Jeffrey said, his voice barely a whisper.

Vance looked at him, incredulous. “Jeffrey, he assaulted you.”

“He’s young,” Jeffrey said, his gaze distant. “He’s stupid. He has been given power, but he has no wisdom to wield it. Give him the brig. Sure. Strip his rank. He’s earned that. But don’t kick him out of the Corps.” He turned and looked Vance in the eye. “Send him to me.”

“To you?”

“Send him to my farm,” Jeffrey said, his eyes looking down the hall as if seeing a distant field. “Let him spend a month painting fences and listening to an old man’s stories. Let him learn, firsthand, what that uniform he wears actually costs.” He paused, a thoughtful frown on his face. “If he can survive a month with me, maybe he’ll be worth wearing that camouflage again.”

Vance stared at his old mentor, then a slow smile of pure admiration spread across his face. He shook his head. “You’re a better man than me, Jeffrey. Always were.”

“Not better,” Jeffrey said, tapping his cane on the floor as the elevator doors slid open. “Just older. And I’ve learned that sometimes the only way to truly win a fight is to turn an enemy into a believer.”

The elevator doors closed, sealing the three generals and the old hero inside, leaving the hallway buzzing with the residual electricity of what had just occurred. The legend of the man in the blue shirt would be told on that base for generations. The day the generals ran. The day the base locked down. The day a bully learned that true valor doesn’t need a uniform to shine.

In the weeks that followed, a subtle but profound change rippled through Fort Independence. The story spread like wildfire, whispered in mess halls, retold in barracks, and discussed in hushed, reverent tones in the officers’ club. Did you hear about Warner? Did you see what happened to Miller?

An official memo was circulated from General Vance’s office mandating a new, rigorous training module on military history, customs, and courtesies for all ranks. But it was more than that. The culture itself shifted. Young soldiers and Marines started to look at the civilian contractors and the elderly volunteers at the base hospital differently. They held doors. They offered greetings. They stopped assuming and started asking. They began to see not just obstacles or old people, but stories.

And one month later, on a small, quiet farm just outside the perimeter of the base, a former corporal named Michael Miller, dressed in worn jeans and a sweat-stained t-shirt, was painting a long white picket fence under the hot Virginia sun. He looked tired. He looked thinner. But most of all, he looked humbled.

On the porch, sitting in a rocking chair with a tall glass of iced tea sweating in his hand, sat Jeffrey Warner. He wore his favorite blue shirt. He watched the young man work, his expression unreadable.

“Missed a spot,” Jeffrey called out, a mischievous twinkle in his pale blue eyes.

Miller stopped painting. He straightened up, using the back of his forearm to wipe the sweat from his brow. He looked at the old man on the porch, and for the first time, his eyes held no anger, no resentment—only a deep, quiet, and profound respect.

“Yes, Sergeant Major,” Miller said, his voice clear and steady.

He dipped his brush back into the can of white paint and went back to work, grateful for the sun on his back, grateful for the fence that needed painting, and grateful, finally, to be serving something far bigger than himself.