Maya Rodriguez met the eyes of her own reflection in the fractured bathroom mirror of her Queens studio apartment. At twenty-four, she was armed with a computer science degree from a state school and saddled with debt that felt more oppressive than the humid New York morning air pressing in on her window. A stack of her mother’s medical bills lay on the kitchen counter, a growing tower of white envelopes that had multiplied since the cancer diagnosis.

“You can do this,” she whispered, her voice a fragile promise to herself as she straightened the collar of her only interview suit. The material was a little worn, the color slightly faded, but it was immaculate. Today had to be different. Today had the potential to change everything. Her phone vibrated—a text from her mom in Phoenix. Feeling good today, sweetheart. Go show them what my daughter is made of. A knot formed in Maya’s throat. Her mother had no idea about the eviction notice tucked discreetly behind that pile of bills, nor did she know that Maya’s diet for the last three weeks had consisted of ramen noodles and sheer hope. Some burdens were meant to be shouldered alone.

The subway journey into Manhattan felt like an eternity. Maya gripped her worn leather portfolio, her fingers tracing its edges as she mentally rehearsed her presentation for the hundredth time. Technova Solutions was one of the fastest-growing startups in the city. The junior developer role wasn’t glamorous, but it was a foothold. More importantly, it was a salary of $65,000 a year—enough to keep the power on, enough to help her mother continue her fight.

“Next stop, 42nd Street,” the conductor’s voice crackled over the intercom. Maya’s heart pounded a frantic rhythm against her ribs. This was it. She ascended from the subway station at 8:45 a.m. Her interview was at 9:30. The timing was perfect, leaving her enough of a buffer to get a coffee, go over her notes one final time, and stride into that office radiating a confidence she didn’t entirely feel.

The morning air was alive with the familiar symphony of the city: the blare of car horns, the distant rumble of construction, the ceaseless shuffle of feet belonging to people chasing their ambitions. Maya had been a part of that frantic rhythm for two years, ever since she’d graduated. It had been a blur of part-time gigs, freelance projects that barely covered her rent, and a steady stream of rejection emails that all began with the polite dismissal, “Thank you for your interest.”

But today was different. She was wearing her lucky earrings, the small silver hoops her grandmother had given her before she passed away. For courage, her grandma had said. Maya glanced at her phone as she turned onto 41st Street. It was 8:52. She was still in good shape.

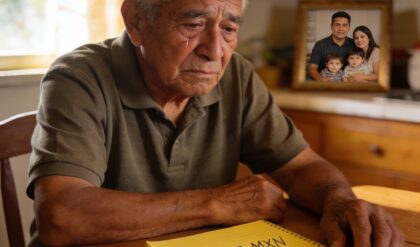

And that’s when she saw him. An elderly gentleman, perhaps seventy-five, stood at the crosswalk, his posture radiating confusion and distress. His white button-down shirt was neatly pressed but creased from travel, and a coffee stain marred his khaki trousers. He held a flip phone—a relic from another era—in his trembling hands, his gaze darting frantically from the tiny screen to the towering street signs.

When he tried to speak to people rushing by, his voice was polite, imbued with the formal cadence of a generation past. Most pedestrians simply streamed around him, their faces set. This was New York; everyone had a destination. Maya found her pace slowing. The man looked genuinely lost. “Excuse me,” she overheard him say to a woman in a sharp power suit. “I’m terribly sorry to bother you, but could you perhaps assist me?” The woman didn’t even break her stride.

Maya checked her phone again. 8:54. The sensible thing to do was to keep moving. She had precisely thirty-six minutes to get coffee, locate the building, clear security, and mentally prepare for the most critical interview of her life. But the man seemed so utterly helpless. His hands weren’t just shaking from confusion; it looked like the onset of something more serious.

“Sir,” Maya said, approaching him gently. “Are you alright? Can I help you?”

The man looked up, and a wave of relief washed over his weathered face. His eyes, a sharp and worried blue, met hers. “Oh, thank goodness. I’m meant to be at a very important meeting, and I’m completely lost. My phone is dead, and all these streets look identical to me.”

Maya glanced at her phone. 8:56. “Where are you trying to go?”

“It’s a tall glass building, I think, near Bryant Park. Or was it Grand Central?” He paused, his brow furrowing with effort. “I’m supposed to meet my son for a board meeting. It’s very important company business.” He spoke of “board meetings” and “company business” not with the unfamiliarity of an outsider, but with the quiet authority of someone who belonged in those rooms.

Maya took out her phone. “Do you recall the name of the building?”

The man’s face fell, crumpled by frustration. “I wrote it down…” He patted his pockets in a frantic search. “The Goldman building… Morrison… Oh, dear, I can’t remember. My son will be so worried.”

Maya’s own heart sank. This wasn’t a simple case of needing directions. “Do you have your son’s number?”

“Yes, it’s in my phone, but the battery died,” he said, holding up the ancient device. “These new phones are too much for me. This one was complicated enough.”

Maya’s phone showed 9:00. “Sir, I really want to help, but I have an appointment at 9:30.”

“Oh, no, my dear. Please, don’t let me hold you up. I’ll sort something out.”

But Maya saw the lost look settle back onto his face. She thought of her grandmother, who had grown confused near the end of her life. She thought of all the elderly people rendered invisible by a city that moved too quickly to notice them. She took a deep breath and began typing on her phone. “Just give me one second,” she said.

She composed a quick email to Technova’s HR department. Emergency situation—assisting an elderly person in distress. May be 30 minutes late. Will call with an update. My sincerest apologies, Maya Rodriguez. She put her phone away, her focus now entirely on the man. “Okay, let’s work through this. You said a glass building. What else can you remember?”

They spent the next ten minutes piecing together fragments of his memory. At last, his face brightened. “Meridian! The Meridian building on Lexington Avenue. That’s it!”

Maya’s stomach plummeted. The Meridian building was a full twenty blocks southeast of where they stood.

“I remember now,” the man went on. “My son, David, works there. He has a critical board meeting at 9:15, and I promised I would be there.”

Maya looked at her phone. It was 9:10. “Sir, that’s quite a distance from here. And if your son’s meeting is at 9:15…”

“Oh, no.” The man’s face turned pale. “I’ve ruined everything, haven’t I? He’s been preparing this presentation for months.” Maya saw the genuine anguish in his eyes; this was about more than just being late.

“Come on,” she said, taking his arm with a gentle firmness. “Let’s get you to your son.”

She hailed a taxi and helped the man into the back seat. As the car pulled into traffic, she gave the driver the address and watched the meter spring to life. It was already at $12. Maya had exactly $37 in her checking account.

“You’re an angel,” the man said. “What is your name, my dear?”

“Maya Rodriguez.”

“I’m Robert. Robert Hartwell.” He paused, gazing out at the blur of the city. “And what were you in such a hurry for this morning, before you stopped for a confused old fool?”

“A job interview, actually. A pretty important one.”

Robert’s expression fell. “Oh, my goodness. And I’ve made you late. What time was it?”

“9:30.”

Robert checked his watch, his hands still unsteady. “It’s 9:20. And the traffic is dreadful.”

Maya pulled out her phone and called Technova. “This is Maya Rodriguez. I sent an email about a delay. I’m helping someone with what might be a medical emergency and—”

“I’m sorry,” the receptionist cut in, her voice crisp and final. “We can’t hold the interview slot. We’re on a very tight schedule today.”

“Please, could you at least keep my resume on file? I know I—”

“I’ll make a note, but I can’t make any promises.”

Maya hung up and stared blankly at her phone screen. The opportunity she had poured months of hope into was dissolving in real-time.

“I feel just terrible about this,” Robert said softly.

“Don’t,” Maya replied, surprised by the calmness in her own voice. “I made a choice.”

The taxi meter continued its relentless climb: $18, $22, $28. When they finally pulled up in front of the Meridian building, the fare was $31. Maya handed the driver all the cash she had, leaving her with just enough for a MetroCard refill to get home.

As they entered the lobby, a security guard looked up and his demeanor instantly changed. “Mr. Hartwell, there you are. Your son was getting concerned. Let me take you up.” Maya registered the guard’s immediate recognition. This was not just any lost old man.

“Wait,” Robert said, fumbling in his jacket pocket. He produced a business card. “My son’s card. Perhaps… perhaps he could help you with that interview.”

Maya accepted the card, giving it a cursory glance. David Hartwell, Senior Vice President, Hartwell Industries. She was too consumed by the wreckage of her morning to fully register the name. “Thanks, but I don’t think anything can help with this one.”

“You never know,” Robert said. “Sometimes life has a way of surprising you.”

She watched him disappear into an elevator with the guard, then found herself standing alone in the cavernous marble lobby. She looked at the expensive art on the walls, the quiet, efficient hum of serious commerce. Then she walked back outside and began the long journey to the nearest subway, on foot, because she’d just spent her last $31 on a stranger. The walk gave her time to process what she had done, and what she would do next.

Her phone buzzed. A text from her mom. How did it go, sweetheart? Maya stared at the words for a long moment before she typed her reply: Still waiting to hear.

The ride back to Queens was a funeral procession for her hopes. She sat in her interview suit, an island of failure surrounded by afternoon commuters who all seemed to have a purpose and a destination. It was after one o’clock when she finally reached her apartment. Maya collapsed onto her secondhand couch and gave herself exactly ten minutes to wallow in self-pity.

Then she stood up, changed her clothes, and started making calls. “Rose’s Diner, this is Maya. I know I’m not on the schedule, but do you have any open shifts?”

“Maya, yeah. Jimmy called in sick. Can you be here by five for the dinner rush?”

“I’ll be there.”

She spent the afternoon walking through her neighborhood, leaving her résumé at any business that looked like it might be hiring. She also sent one last email to Technova.

Dear Hiring Team, I want to be transparent about what happened this morning. I was delayed helping an elderly man, who appeared to have early-stage dementia, find his way to an important meeting. I chose to prioritize someone in immediate need over my own professional opportunity. I understand and accept the consequence of missing my interview. I hope you might consider my qualifications for future openings. Sincerely, Maya Rodriguez.

At 4:30, she pulled on her Rose’s Diner uniform and went to work. The shift was brutal: eight hours on her feet, juggling demanding customers and a kitchen that was always behind schedule. Her back ached, her feet throbbed, and she smelled of fryer grease and regret. But it was money. Forty-two dollars in tips, plus her wage. She didn’t get home until 2:00 a.m. and fell into bed, too exhausted to even shower.

Her alarm blared at 8:00 a.m. Maya dragged herself up, showered, and sat at her kitchen table, methodically applying for jobs online. At 10:30, her phone rang. An unknown number.

“Hello?”

“Is this Maya Rodriguez?”

“Yes. Who is this?”

“This is David Hartwell. I believe you helped my father yesterday.”

Maya’s breath hitched. “Is he okay? Did he make it to your meeting?”

“He did, thanks to you. He walked into our boardroom twenty minutes late, apologizing profusely and telling everyone about the remarkable young woman who saved his day.” David’s voice was warm, yet professional. “Maya, I would like to meet with you, if you have a moment.”

“I… yes. But why?”

“I can explain when we meet. Are you available this afternoon?” He paused. “My father has early-stage dementia. Yesterday’s board meeting was crucial for our company. When he didn’t arrive, I was frantic. When he finally showed up and told us what happened, I realized something important.”

“What was that?”

“You had no idea who my father was, did you?”

“Not until he gave me your card.”

“Exactly. You helped him because it was the right thing to do, not for any personal gain.” David was quiet for a second. “Maya, what kind of work do you do?”

“I’m a software developer… or I’m trying to be. I specialize in user experience and interface design.”

“Would you be interested in coming in for a conversation? Not an interview, exactly. More of a discussion about a project we’re developing.”

Maya stared at her laptop, at the long list of submitted applications, afraid to let herself hope. “What kind of project?”

“Technology solutions for the aging population. We’re trying to build products that actually serve seniors instead of frustrating them.” David paused again. “The challenge is that most of our developers don’t truly grasp the problems older adults face. Yesterday, you demonstrated precisely the kind of perspective we’re missing. When can you meet?”

“How about tomorrow afternoon? Two o’clock.”

Maya dedicated the rest of her day to researching Hartwell Industries. The scale of the company was staggering: a massive conglomerate with interests in technology, healthcare, and real estate, with annual revenues in the billions. And David Hartwell wasn’t just an SVP; he was the heir apparent, being groomed to take over as CEO.

The next afternoon, Maya stood in the lobby of the Hartwell Industries building, which made the Meridian building look modest. Fifty stories of glass and steel soared into the sky. David Hartwell’s office was enormous, with floor-to-ceiling windows offering a panoramic view of Central Park. He was younger than she’d expected, maybe forty, with kind eyes and a welcoming smile.

“Maya, thank you for coming in,” he said, rising from behind a desk that likely cost more than her yearly rent. “Please, sit.”

Maya settled into a leather chair, trying to ignore how profoundly out of place she felt.

“First,” David began, “I want to thank you again for what you did for my father. He means the world to me, and it’s been difficult watching him struggle to maintain his independence.”

“I can imagine it must be very hard.”

“Yesterday was especially tough. He was supposed to present our new senior care initiative to the board. When he got lost, I thought we’d lost our chance.” David leaned forward. “But then he walked in and delivered one of the most compelling presentations I have ever seen.”

“About what?”

“About dignity. About how technology should empower people, not confuse them. About the importance of seeing seniors as individuals with a lifetime of experience, not as problems to be solved.” David smiled. “He said he learned it all from a young woman who treated him like a person worth helping.”

Maya felt a warmth spread across her cheeks. “He’s a remarkable man.”

“He is. And he’s also the majority shareholder of this company.” David rose and walked to the window. “Maya, I’ve been searching for someone to lead our senior technology initiative. Someone with the technical skills, certainly, but more importantly, someone who understands that technology is ultimately about people.”

Maya’s pulse began to race. “What would that role involve?”

“Leading a small pilot project to start. Ninety days to prove the concept with real users and hard metrics.” He turned back to face her. “If it’s successful, we’ll expand it into a full division.”

“What’s the timeline?”

“The first thirty days: user research and prototyping. Days thirty-one to sixty: pilot testing with fifty senior users. The final thirty days: analysis and recommendations.” He sat back down. “At the end of the ninety days, if the metrics hold up, we’d offer you a permanent position as head of the team.”

The room felt like it was tilting. “And the salary… during the pilot?”

“Consultant rate. Seventy-five dollars an hour, forty hours a week. If you convert to a permanent role, we’d start you at eighty-five thousand, plus equity.”

Maya did the math in her head. $75 times 40 hours times 12 weeks was $36,000—more than she had earned in the entire previous year. “But I have no experience leading projects.”

“You have something more valuable: empathy. And you proved yesterday that you put people ahead of personal gain.” David slid a folder across the desk. “I’ve looked at your portfolio, your GitHub, your academic recommendations. You’re talented, Maya. The only question is whether you’re ready for this challenge.”

She thought about her mother’s fight with cancer, the eviction notice, the greasy smell of the diner, and Robert Hartwell, lost on a street corner. “What happens if I fail?”

“Then you fail. The pilot ends. We pay you for your time, and you walk away with ninety days of experience at one of the country’s largest corporations.” David smiled. “But I don’t think you’re going to fail.”

“Why not?”

“Because you’ve already passed the most important test. You chose to help when it cost you something. The rest is just execution.”

Maya looked out at Central Park, at the vast expanse of green, and thought of the winding path that had led her here. “I’m interested,” she said.

“Excellent. You’ll be working with Sarah Kim, our VP of Product Development. She’ll be your mentor.” He handed her the folder. “Your first assignment is inside. Background research, interview guidelines, success metrics.”

Maya opened it to find pages of detailed specifications, budget outlines, and project milestones. This wasn’t an act of charity. This was a real job with immense expectations.

“When do I start?”

“Monday morning. 8:00 a.m.”

Maya spent the weekend oscillating between disbelief and sheer terror. This was the opportunity of a lifetime, but it came with a level of pressure she had never known. Failing at Rose’s Diner meant a spilled coffee; failing here meant squandering a chance she hadn’t earned through any traditional means.

Monday morning was gray and drizzly. At 7:45, Maya stood outside the Hartwell building, wearing her interview suit and holding a new notebook purchased with her diner tips. Sarah Kim, a sharp and efficient woman in her forties, met her in the lobby and got straight to the point. “Maya, welcome. I’ve read David’s notes. Ready to begin?”

They rode the elevator to the 38th floor, where Maya was introduced to her team: two junior developers, a UX designer, and a data analyst, all with more conventional résumés than hers.

“Maya will be leading our senior user experience pilot,” Sarah announced. “She’ll be working directly with end users to understand their needs.” Maya felt the weight of their skeptical glances. She was the youngest person in the room, leading a project for users older than anyone present.

“Where do we start?” asked Josh, one of the developers.

Maya surveyed the conference room: whiteboards filled with technical jargon, laptops displaying sleek mock-ups, charts detailing user acquisition funnels.

“We start,” Maya said, her voice clear and steady, “by admitting we have no idea what we’re talking about.”

The room fell silent.

“I’m serious,” she continued. “We’re all under forty, building tech for people over sixty-five. When was the last time any of us spent real time with someone that age, just watching them navigate their daily challenges with technology?”

“We have user surveys,” the UX designer offered defensively.

“Written by whom? Reviewed by whom? Distributed how?” Maya walked to the whiteboard. “Here’s our first assignment. This week, each of you will spend at least four hours with someone over seventy. Not to interview them. Just to be with them, to observe how they interact with technology in their own environment.”

“That seems inefficient,” Josh countered.

“Efficient for whom?” Maya asked. “For us, or for the people we’re supposed to be helping?”

In the weeks that followed, Maya immersed herself in understanding their target users with an intensity that began to win over her team. She visited senior centers, listened in on tech support calls, and spent countless hours observing how older adults used websites and apps. What she discovered dismantled all her preconceived notions.

Margaret, 78, wasn’t baffled by technology; she was frustrated by interfaces that ignored her physical limitations. Her arthritis made tapping small buttons a painful chore. Frank, 82, didn’t avoid online banking because he feared for his security, but because the systems demanded he recall trivial details from decades past. Eleanor, 74, had been a computer programmer in the 1970s and felt patronized by modern interfaces that spoke down to her.

“We are not designing for deficits,” Maya declared to her team after two weeks. “We are designing for different capabilities and preferences.”

Their first prototype was a dismal failure. Maya watched as Frank struggled with their “simplified” interface for five minutes before giving up. “The buttons are bigger, but they still don’t mean anything,” he said, his voice edged with frustration. “Why do I have to click ‘share’ to call my daughter? Why can’t the button just say, ‘Call Sarah’?”

Maya’s stomach clenched. They had made everything bigger and brighter, but they hadn’t made it more meaningful. “Back to the drawing board,” she told the team.

“We’re running out of time,” Josh warned. “We’re three weeks in.”

“We’re not running out of time,” Maya corrected him. “We’re learning. Would you rather ship a product that doesn’t work, or take the time to build one that does?”

The second prototype was radically different. It abandoned generic actions like “share” and “connect” in favor of buttons labeled with specific intentions: Call My Son, Send Photo to Grandchildren, Schedule Doctor Visit. Instead of cramming in the latest features, the team focused on making the most common tasks effortless.

The results were dramatic. In their 50-user pilot test, engagement rates were three times higher than with the first version. More importantly, users were successfully completing their goals.

“This is promising,” Sarah conceded during their six-week review. “But the CFO is asking tough questions about cost per acquisition and lifetime value. Seniors are not a demographic known for spending heavily on tech.”

This was the conversation Maya had been preparing for. “What kind of numbers does he need to see?”

“Customer acquisition cost under fifty dollars, lifetime value over three hundred, and proof that this demographic will pay for premium features.”

Maya spent the next week buried in data she’d never had to consider before: healthcare utilization, medication adherence, family communication patterns. Her findings surprised everyone.

“Seniors aren’t valuable as tech consumers,” Maya explained to the executive team a week later. “They’re valuable as healthcare consumers. Our users are showing a twenty percent increase in medication adherence and a fifteen percent reduction in emergency room visits. That’s worth thousands of dollars a year per user to insurance companies.”

David leaned forward. “You’re suggesting a B2B model.”

“I’m suggesting we solve the right problem. Seniors want to preserve their independence. Healthcare systems want to cut costs. Our platform achieves both.”

The CFO remained skeptical. “Where’s the revenue?”

“Healthcare partnerships. Insurers will pay for platforms that demonstrably improve health outcomes. Adult children will pay for services that help them care for their aging parents remotely.” Maya advanced to her next slide. “Our pilot users generated an average of four hundred dollars in healthcare savings per quarter. If we scale that, we’re looking at a hundred-million-dollar opportunity.”

The room was quiet. “Impressive analysis,” the CFO finally said. “How confident are you in these projections?”

“Confident enough,” Maya replied, “to stake my permanent employment on them.”

Three months after she had missed her interview at Technova, Maya stood on a stage at the Senior Technology Conference in Las Vegas. Her 90-day pilot had not only been a success; it had shattered every metric David had established.

“Our final presenter is Maya Rodriguez from Hartwell Industries,” the moderator announced. “She’ll be discussing their human-centered approach to senior technology.”

Maya walked to the center of the stage and looked out at an audience of eight hundred people. In the front row, she saw Robert Hartwell, his face beaming with pride.

“How many of you,” Maya began, “have ever had a young person try to help you with technology?” Hundreds of hands shot up amid knowing laughter. “And how many of you have had that person become frustrated when you didn’t immediately understand?” Even more hands went up. “That’s because we’ve been looking at this problem backwards. We assume older adults need simpler technology. But what you really need is more intentional technology.”

She walked the audience through their research, their design philosophy, and the users who had shaped every decision. Then came the moment she’d been preparing for. A man in the third row stood up. Maya recognized him as the CEO of AgeTech Solutions, Hartwell’s largest competitor.

“Your approach sounds lovely,” he said, “but how do you scale it? How do you maintain that personal touch with millions of users?”

This was the test. “That’s a great question,” Maya said calmly. “And you’re right, our initial pilot was small. But we didn’t stop there.” She clicked to a new slide, revealing a diagram of their scaled research process. “We now have a panel of two hundred senior collaborators across twelve cities. They are paid consultants who review every design decision and test every new feature through structured protocols.” She clicked again. “We’ve also developed open-source design guidelines—specific button sizes, color contrasts, and language patterns that work for older adults. This isn’t about empathy; it’s about systems. Our research budget is three percent of our development costs. In return, we have ninety-two percent user satisfaction and sixty-eight percent six-month retention.” She paused, looking directly at him. “How do your numbers compare?”

The room was silent. AgeTech’s poor retention rates were widely known.

“Finally,” Maya concluded, “we are open-sourcing our research because this isn’t about competitive advantage. It’s about building technology that serves the people who use it.”

The applause was thunderous and genuine. Afterward, Maya was surrounded by people from healthcare organizations wanting to partner and investors asking about expansion. But the most meaningful conversation was with Robert Hartwell.

“You did something remarkable up there,” he said, his voice steadier than it had been on that street corner. “You showed them we’re not problems to be solved. We’re people to be understood.”

“I learned that from you,” Maya replied.

Robert smiled. “No, my dear. You already knew it. I just gave you a chance to prove it.”

Six months later, Maya was back in David’s office. Her pilot had blossomed into a division of fifteen people, their platform now serving over 20,000 seniors.

“Maya, I want to discuss the next phase,” David said. “We want to expand your human-centered approach across all our healthcare products. It would mean leading a team of forty, with a budget of fifteen million dollars.”

That old flicker of imposter syndrome returned. “I’ve only been here six months.”

“And in that time, you’ve built our most successful healthcare product, not just by revenue, but by real-world impact.” David smiled. “Are you ready for the challenge?”

Maya thought of that morning seven months ago, standing at a crosswalk, calculating the price of compassion. She thought of her mother, whose cancer treatments were now covered by Maya’s Hartwell health insurance. She thought of Margaret, Frank, and Eleanor, who had gone from being users to collaborators to friends. She thought of all the problems still left to solve. “I’m ready,” she said.

That evening, she called her mother to share the news. “I’m so proud of you, sweetheart,” her mother said. “But can I ask you something? Do you ever wonder what would have happened if you’d just walked past that man?”

Maya looked out her window at the city lights—a much nicer window, in a much nicer apartment. “Sometimes,” she admitted. “But then I remember something Grandma used to say. She said the most important opportunities don’t look like opportunities. They look like interruptions. And I’ve learned that who you are is the person you choose to be when no one is watching. Everything else is just circumstance.”

Her mother was quiet for a moment. “You chose to be the person you wanted to be.”

“I chose to be the person you and Grandma raised me to be.”

After hanging up, Maya reflected on her journey. She had once believed that morning was about a choice between her future and a stranger’s need. She saw now how wrong she had been. She hadn’t sacrificed her future to help Robert Hartwell; she had discovered it. The lesson wasn’t about karma or good deeds being rewarded. It was simpler: opportunities rarely announce themselves. They often arrive disguised as inconveniences, as disruptions to well-laid plans, as moments that force a choice between what is expedient and what is right.

Maya had made that choice on a busy Manhattan street. She made it again when she scrapped a failed prototype and when she listened to users instead of assuming she knew best. She would keep making it, one small decision at a time, building a world where technology served people, and not the other way around. Outside her window, the city hummed, a million stories unfolding at once. Maya knew exactly which story was hers. She had known it the moment she stopped walking. Everything else was just the consequence of that one choice, rippling outward in ways she could never have imagined. And it was only the beginning.