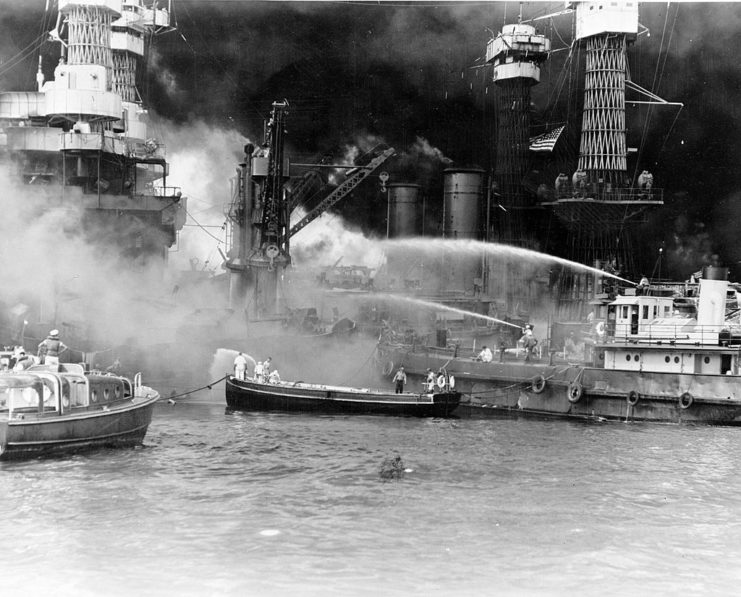

Three Sailors Were Trapped Inside a Battleship Following the Attack on Pearl Harbor

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese launched a devastating attack on US naval forces based at Pearl Harbor. Approximately 2,400 sailors and Marines lost their lives that day, including three whose stories are relatively unknown.

USS West Virginia, 1940s. (Photo Credit: Frederic Lewis / Getty Images)

When the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, the USS West Virginia was positioned outboard of the USS Tennessee as part of Battleship Row, along with the USS Arizona, California, Pennsylvania, Nevada, Maryland and Oklahoma. A repair vessel, the USS Vestal, was also moored beside the Arizona.

The USS West Virginia was hit by two overhead bombs and at least six torpedoes during the attack. Immediately after, officers aboard the ship called a “setting condition Zed,” a naval technique wherein all hatch compartments are closed and a portion of the ship flooded to keep it from capsizing.

It was ablaze for 30 hours before sinking and settling along the bottom of the harbor, 40 feet below the water. According to the National Park Service, 106 crew members were killed.

Explosion at the Naval Air Station during the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Photo Credit: Fox Photos / Getty Images)

The following day, those who’d survived the attack began cleanup efforts, during which they heard a banging noise coming from the USS West Virginia. At first, they thought it was a piece of loose rigging hitting the hull. However, they soon realized they were hearing the sounds of those trapped inside the wreckage.

“When it was quiet you could hear it… bang, bang, then stop. Then bang, bang, pause. At first, I thought it was a loose piece of rigging slapping against the hull. Then I realized men were making that sound – taking turns making noise,” said bugler Dick Fiske.

Sailors recounted how they dreaded guard duty close to the USS West Virginia, as they could hear the trapped men. Unfortunately, there was nothing anyone could do to rescue them. The risk was too high: cutting a hole in the hull would cause it to fill with water, while using a torch brought about the risk of explosion.

Clifford Olds (right), photographed tonight 1941, died on USS West Virginia after Pearl Harbor attack the next day: pic.twitter.com/08IBCmT5AK

— Michael Beschloss (@BeschlossDC) December 6, 2016

The USS West Virginia was raised six months later. Within it, salvage crews found the bodies of three men huddled together in storeroom A-111: 18-year-old Ronald Endicott of Washington; 21-year-old Louis “Buddy” Costin of Indiana; and 20-year old Clifford Olds of North Dakota.

Also found were flashlight batteries, a manhole to supply fresh water and the remnants of emergency rations. There was also a calendar, with sixteen days crossed off in red pencil: December 7 to December 23. It turned out the three had been stuck in the wreckage, alive, for over two weeks, without the ability to escape.

USS West Virginia on fire after being hit during the attack on Pearl Harbor. (Photo Credit: Universal History Archive / UniversalImagesGroup / Getty Images)

Word of the discovery spread quickly through Pearl Harbor. However, the Navy never told their families how long they’d been alive. It wasn’t until decades later, in 1995, that their loved ones learned the truth when Honolulu Advertiser‘s Eric Gregory wrote a piece about the attack.

Following its discovery, the calendar was sent to the chief of naval personnel in Washington, D.C., and its current location is unknown. Following their recovery, Endicott and Costin were buried at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific – known as the “Punchbowl” – in Honolulu. Olds’ remains were returned to his hometown and buried in the local cemetery.

All three of their headstones say they died on December 7, 1941, the day of the attack.

National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. (Photo Credit: Gerald Watanabe / Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Following it being raised, the USS West Virginia was repaired. When it was returned to service in April 1944, it played a key role in the US forces’ efforts against Japan, and was present at Tokyo Bay during the Japanese surrender. It was decommissioned in 1957 and sold for scrapping two years later.

News

The “Red Zone” – Land Still Abandoned Due to the Dangers Left by the First World War

The “Red Zone” – Land Still Abandoned Due to the Dangers Left by the First World War In the aftermath of the First World War, large areas of northeast France were left in ruin. Years of constant siege warfare along…

Before Becoming a Big-Name Actor, Richard Todd was a Paratrooper Who Fought at Pegasus Bridge

Before Becoming a Big-Name Actor, Richard Todd was a Paratrooper Who Fought at Pegasus Bridge Photo Credit: 1. Sgt. Christie, No. 5 Army Film & Photographic Unit / Imperial War Museums / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain 2. Silver Screen…

The Potsdam Giants: A Prussian Infantry Regiment Of Nothing But Very Tall Soldiers

The Potsdam Giants: A Prussian Infantry Regiment Of Nothing But Very Tall Soldiers Frederick William I inspecting his giant guards known as The Potsdam Giants, a Prussian infantry regiment No 6, composed of taller-than-average soldiers. Frederick William I of Prussia,…

Ellen DeGeneres cuts a very casual figure as she drives around in her Ferrari

Ellen DeGeneres cuts a very casual figure as she drives around Montecito in her Ferrari… while preparing to embark on her stand-up tour Ellen DeGeneres cut a very casual figure as she made her way around Montecito on Tuesday morning. The…

“I’m heavily tattooed and keep getting rejected for jobs – it’s not fair”

Heavily tattooed OnlyFans star, 23, with multiple piercings on her FACE slams TJ Maxx for rejecting her for a job – accusing retailer of unfairly judging her dramatic look A woman has accused TJ Maxx of rejecting her for a…

All 75 passengers killed in plane crash after pilot let his chirldren control the plane

Praying, turning the engine off by accident and letting KIDS play with the controls: The worst blunders made by pilots before a crash revealed Every time we board a plane, we put our lives in the hands of the pilot….

End of content

No more pages to load