I was sixteen years old, sitting in a converted basketball court that smelled of floor wax and collective judgment, while two hundred strangers waited for me to break. They called it an “academic review.” It was actually a public execution of my character. My crime? Writing a college essay about my mother. To them, she was a ghost, a deadbeat who abandoned me for a desk job in nowhere-ville. To the school board, I was a “pathological liar” inventing a hero to cope with trauma. To the town psychiatrist, I was a “case study.” But as the Superintendent waved my essay like a weapon and the crowd laughed at the idea of a woman being a Navy SEAL, none of them noticed my grandfather checking his watch. They didn’t know about the black SUV idling outside. And they had no idea that the “lies” I was being persecuted for were about to kick down the double doors and remind them all that silence is not the same as absence.

PART 1: THE SILENT OPERATOR

The first thing you learn when your mother is a ghost is how to control your breathing.

Inhale for four. Hold for four. Exhale for four. Hold for four.

Box breathing. It regulates the autonomic nervous system. It lowers cortisol. It keeps you from screaming when two hundred pairs of eyes are boring into your skull, waiting for you to cry.

I sat at a folding table in the center of the Mercer County Community Center, my hands clasped so tightly together that my knuckles had turned the color of old bone. Above me, the fluorescent lights hummed with an angry, insectile buzz, flickering just enough to induce a migraine. But I didn’t blink. I didn’t slouch. I kept my spine rigid, a steel rod welded to the back of the metal chair, just the way she had taught me before she vanished again.

“This character assessment hearing is now in session.”

The voice belonged to Superintendent Loel Hargrove. He sat behind a raised dais that had been hastily constructed on the stage, flanked by four members of the Board of Education. They looked like a panel of inquisitors from a dystopian novel, looming over me. The microphone screeched, sending a spike of feedback through the room, and I saw people in the back row wince.

There were so many of them. That was the part I hadn’t calculated.

The letter they’d sent to my grandfather said this was a “private academic review” to discuss “irregularities” in my college application packages. Yet, somehow, half the town had found out. The bleachers were pulled out. Neighbors I’d known my whole life—people who bought girl scout cookies from me, people who waved at me in the grocery store—were packed in shoulder-to-shoulder, whispering. They weren’t here for the truth. They were here for the spectacle. They were here to watch the weird, quiet girl from the edge of town finally crack.

“We are here,” Hargrove announced, his voice dripping with a faux-solemnity that made my stomach turn, “to address concerns regarding Embry Callister’s college application materials. Specifically, her personal essay.”

He paused, letting the silence stretch until it felt heavy, suffocating. He held up the stapled sheets of paper as if he were holding a contagiously diseased object.

“Which contains… questionable claims.”

A ripple of murmurs moved through the crowd. I heard a snicker from the left—the high school quarterback, probably. Or maybe one of the PTA moms who always looked at my grandfather with pity.

Inhale for four.

I didn’t look at Hargrove. I shifted my gaze, scanning the sea of hostile faces until I found the only anchor I had left.

Retired Colonel Thaddius Callister sat in the very back row, near the exit. He was wearing his Sunday suit, charcoal gray, pressed to a razor’s edge. His silver crew cut was severe, his face a mask of granite. To anyone else, he looked bored, maybe even ashamed. But I saw the micro-expressions. I saw the way his jaw muscle feathered, just once. He caught my eye and gave a nod so imperceptible that if I hadn’t been trained to look for it, I would have missed it entirely.

Stay strong. Hold the line. Give nothing away.

“Ms. Winslett,” Hargrove said, gesturing to the side. “Please.”

My English teacher stepped up to the microphone stand positioned a few feet from my table. She looked miserable. Ms. Winslett had always been kind to me, in that pitying way teachers are kind to the kid who eats lunch alone in the library. She clutched a copy of my essay, her fingers trembling slightly. She didn’t want to be here. She was being used as the weapon.

“I… I’ve been asked to read portions of Miss Callister’s essay,” she stammered.

“Proceed,” Hargrove commanded.

She cleared her throat. When she began to read, it was my words, but stripped of my voice. She made them sound fantastical. Absurd.

“While other mothers attended PTA meetings, mine was deployed with the Naval Special Warfare Development Group. While other mothers taught their daughters to bake, mine taught me to swim with weighted ankles and hold my breath for three minutes. My mother, Commander Zephyr Callister, was among the first women to complete SEAL training, though her existence remains classified…”

The laughter started in the front row. It wasn’t loud, just a sharp, incredulous exhalation. But it spread. It rippled backward like a wave, growing in volume.

“SEAL training?” someone whispered loud enough to be heard. “Yeah, right. And my dad is Batman.”

“Pathological liar,” another voice said. It was a woman’s voice. Harsh. Judgmental.

I focused on the wood grain of the table. I remembered the water. The cold, dark water of the quarry behind our house. I remembered being ten years old, the heavy velcro weights dragging my ankles down into the silt. I remembered the burning in my lungs, the panic rising in my chest, and then I remembered her hand grabbing my shoulder, steady and strong.

Panic is a choice, Embry. Oxygen is a resource. Manage your resources.

I wasn’t lying. I had the scars on my ankles to prove it. I had the lung capacity of a pearl diver. I knew how to disarm a man twice my size using only leverage and gravity. But how do you explain that to a room full of people whose biggest struggle is finding a parking spot at the mall?

“That’s enough, Ms. Winslett,” Hargrove interrupted, looking pleased with the reaction he’d incited. He turned his head toward a man in a tweed jacket sitting at the end of the table. “Dr. Fleming. Your professional assessment?”

Dr. Fleming was the town psychiatrist. I had never spoken to him in my life, yet he adjusted his glasses with the confidence of a man who claimed to know the inside of my soul.

“I believe,” Fleming said, his voice smooth and practiced, “that we are witnessing a textbook case of compensatory fantasy formation.”

He looked at the crowd, playing to his audience. “Given the extended absence of her mother—an absence that has spanned nearly the child’s entire life—Embry has constructed an elaborate alternative reality. It is a coping mechanism. She reframes abandonment as heroic service. If her mother is a secret super-soldier, then her mother didn’t leave her. Her mother is saving the world. It’s a tragic, but common, delusion.”

The word hung in the air. Delusion.

It felt like a physical slap. I looked up then. I broke protocol.

“I haven’t been abandoned,” I said. My voice was quiet, but the acoustics of the gym carried it. “And I haven’t lied.”

Hargrove smiled. It was a thin, reptilian stretching of lips that didn’t reach his eyes. “Then perhaps, Miss Callister, you can explain this.”

He produced a folder. It was thick, official-looking. He pulled out a document stamped with the Department of the Navy seal.

“We obtained your mother’s naval service record through proper channels,” Hargrove announced, waving the paper. “Zephyr Callister. Rank: Administrative Specialist. Duty Station: Naval Support Facility, Diego Garcia. Honorable discharge eight years ago.”

He leaned forward, his eyes gleaming with triumph. “Not a single notation about special operations. Not one deployment to a combat zone. She was a clerk, Embry. A clerk who filed paperwork in an office, quit eight years ago, and hasn’t bothered to come see you since.”

The crowd erupted. This wasn’t just murmuring anymore; it was full-blown ridicule. They felt justified now. They had the paperwork. I was just a sad, lying little girl.

“That’s her cover record,” I said.

The laughter exploded. It bounced off the metal rafters. It was a wall of sound, mocking and cruel.

“Cover record,” Hargrove repeated, chuckling. “Like in the spy movies? Intelligence protocols?”

“Yes,” I said, my voice hardening. “Exactly like that.”

“Let’s continue,” Hargrove said, dismissing me with a wave of his hand. He looked past me, toward the back of the room. “Colonel Callister. As Embry’s guardian and Zephyr’s father… surely you want to stop this charade? Would you care to clarify the situation?”

Every head in the room turned. Two hundred people twisted in their seats to look at the old man in the back row.

My grandfather didn’t stand. He didn’t fidget. He sat with the stillness of a statue in a graveyard.

“I have nothing to add to my granddaughter’s statement,” he said. His voice was gravel and iron.

“Nothing to add?” Hargrove pressed, sensing blood. “Or nothing to correct?”

The Colonel lifted his left wrist. He pulled back the cuff of his suit jacket and checked his watch. It was a heavy, tactical piece—analog, not digital. He stared at the face of it for a second too long.

“Nothing to add,” he said, lowering his arm. “At this time.”

At this time.

The phrase sent a shiver down my spine. I glanced at the clock on the wall: 3:47 PM.

Grandfather was checking the time. He wasn’t checking it because he was bored. He was checking it the way he used to check it before we left the house for church, or before a storm hit. He was timing something.

The mermaid swims at midnight. The eagle returns at dawn.

The code phrases echoed in my head. My mother used to call on burner phones, her voice distorted by distance and static. She taught me codes before she taught me nursery rhymes.

“If I may,” a new voice boomed.

Mayor Sutcliffe stood up in the front row, straightening his silk tie. He wanted in on the action. This was political theater, and he was missing his cue. “Given the seriousness of fabricating military service—stolen valor is a crime, young lady—perhaps Embry could enlighten us about these ‘classified missions’ her mother is supposedly leading.”

And so, the interrogation began.

It wasn’t about the college essay anymore. It was a sport. They took turns firing questions at me, trying to trip me up on the details of a life they couldn’t comprehend.

“So these midnight swims,” the Mayor asked, smirking. “What were they for? Training you to be a mermaid?”

“Recovery techniques for water insertions,” I answered, my voice mechanical. I was reciting the manual now. If I stopped to feel, I would break. “Breath-hold diving. Stress inoculation.”

“And you don’t plan to follow her path?”

“No,” I said softly. “I want to study Political Science.”

“Wise decision,” a heckler shouted from the back. “Since the Navy doesn’t hire liars!”

More laughter. It was relentless. It was eroding me, layer by layer.

Then, the squeak of rubber wheels on linoleum cut through the noise.

Warren Pike, the town’s oldest Vietnam veteran, wheeled himself toward the front. He parked his wheelchair in the designated public comment area. Pike was a hard man. He had a face like a topographic map of a war zone and eyes that had seen things these suburbanites couldn’t imagine. He adjusted the hat on his head, the one with the combat ribbons.

The room quieted down out of respect for him. Pike didn’t look at Hargrove. He looked at me.

“I’ve got some questions,” Pike rumbled. “About these… operations.”

I met his gaze. For the first time, I saw something other than mockery. I saw suspicion. He was testing the perimeter.

“What’s the proper protocol for HAHO jumps versus HALO jumps?” he asked abruptly.

The crowd looked confused. They didn’t know the acronyms. But I did. I knew them before I knew long division.

“High Altitude High Opening,” I said instantly. “Requires deployment of the parachute shortly after exiting the aircraft—usually above 30,000 feet—allowing the operator to glide horizontally for up to forty miles to the landing zone. Used for cross-border insertions to avoid radar.”

Pike’s eyes narrowed. “And HALO?”

“High Altitude Low Opening. Free-falling to approximately 2,000 feet before deployment. Minimizes canopy time. Reduces the chance of detection by ground forces. Higher risk of hypoxia if O2 systems fail.”

Pike didn’t blink. “Equipment check before water infil?”

“Rebreather functionality—Draeger or Mk 25,” I recited, the list flowing out of me like a prayer. “Dry suit integrity. Comms check. Weapons waterproofing. Mission package security. Plus individual team checks based on specialized gear.”

A muscle twitched in Pike’s jaw. He looked at me, really looked at me, and for a second, the hostility vanished. He looked… unsettled.

“That’s something anyone could learn from video games,” Hargrove cut in, his voice loud and irritated. He hated losing control of the narrative. “Dr. Fleming, would this level of detailed fantasy be consistent with your diagnosis?”

The psychiatrist nodded sagely, reclaiming the spotlight. “Absolutely. The more elaborate the fantasy, the more the subject invests in the minutiae. It anchors the delusion. She has likely memorized manuals to legitimize the lie.”

Pike looked at Dr. Fleming, then back at me. He didn’t say anything, but he didn’t join in the renewed laughter either. He just sat there, his hands gripping the wheels of his chair, processing.

“I think we need to address the underlying issue,” Hargrove said. He reached into his folder again. “I have a photograph.”

He held up a blown-up picture. It was grainy, clearly taken from an old ID card. It showed a woman in standard Navy dress blues. She looked young. Her face was blank, administrative.

“This is Zephyr Callister’s official service photo,” Hargrove sneered. “Look at her. Does this look like a SEAL to you? Does this look like a woman who kicks down doors and hunts terrorists?”

He scanned the room. “She’s a secretary, folks. A secretary who left her daughter behind.”

“You don’t know anything about her!” I shouted. I couldn’t help it. The box breathing failed. The dam broke. “You don’t know who she is!”

“We know she’s not here,” Hargrove countered, his voice dropping to a sympathetic coo that was worse than the yelling. “We know she hasn’t attended a single parent-teacher conference. We know she missed your graduation from middle school. We know that fabricating military service is disrespectful to actual heroes. Like Mr. Pike.”

I looked at Pike. He looked down at his hands.

My chest heaved. I felt the tears pricking the corners of my eyes, hot and stinging. I wanted to flip the table. I wanted to scream that the reason she wasn’t here was because she was doing things that kept them safe while they slept in their soft beds.

“Colonel Callister?” Hargrove looked to the back again.

Grandfather checked his watch.

4:13 PM.

He looked at the watch, then he looked at the double doors at the back of the gym. He didn’t look at Hargrove.

“Colonel?” Hargrove asked, annoyed.

“She said someday I’d understand,” I whispered, my voice cracking. The room went silent to hear me fall apart. “She said someday… they’d know she existed.”

“Well,” Hargrove leaned forward, sensing the kill. He spread his arms wide, gesturing to the empty gym floor behind me. “Where is she then, Embry? Where is this phantom mother of yours?”

I closed my eyes. The humiliation was absolute. I was sixteen, and my life was over. I was the town joke.

And then, I heard it.

At first, I thought it was the buzzing of the lights. But it was too rhythmic. Too deep. A thumping sound, vibrating against the metal roof of the community center. Thump-thump-thump-thump.

The glass in the water pitcher on Hargrove’s table rippled.

The sound grew louder. It wasn’t a car. It wasn’t a truck. It was directly overhead.

Hargrove looked up, confused. “What is that noise?”

In the back row, Colonel Thaddius Callister finally stood up. He smoothed his jacket. He looked at Hargrove, and for the first time all afternoon, he smiled. It was a wolf’s smile.

“That,” my grandfather said, his voice cutting through the sudden confusion, “is the extraction team.”

He looked at his watch one last time.

“And they are right on time.”

The double doors of the community center didn’t just open. They were thrown wide with a force that slammed them against the walls.

The hydraulic hiss was audible even over the murmuring crowd.

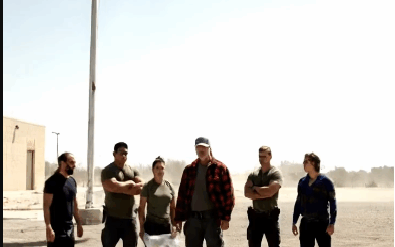

The sunlight from outside poured in, silhouetting figures. Not one. Not two. Six.

They moved as a single organism. Black tactical gear. Drop holsters. Helmets absent, but the bearing was unmistakable. They didn’t walk; they flowed. Boots struck the linoleum in a terrifying, synchronized cadence. Clack. Clack. Clack.

Conversation died instantly. It was as if the oxygen had been sucked out of the room.

The figure in the lead walked with a stride I would know anywhere. Even in the tactical vest, even with the scary intensity radiating off her like heat, I knew that walk.

She marched straight down the center aisle. The crowd parted like the Red Sea, people pulling their legs in, terrified to even touch the fabric of her uniform.

She stopped ten feet from Hargrove’s dais. She looked at him, then she looked at the picture of the “secretary” he was still holding.

She reached up and removed her sunglasses. Her eyes were the same color as mine. Steel gray.

“I believe,” my mother said, and her voice was the coldest thing in that sweltering room, “you have some questions about my attendance record.”

PART 2: THE GHOST IN THE ROOM

The silence in the Mercer County Community Center wasn’t just quiet; it was heavy. It felt like the air pressure had dropped ten millibars in a single second.

Superintendent Hargrove, a man who loved the sound of his own voice, opened his mouth like a fish on a dock. No sound came out. He looked at the woman standing before him—my mother—and then he looked at the five operators fanning out behind her.

They didn’t point weapons at the crowd—that would be illegal, and they were professionals—but they didn’t have to. They moved to the corners of the room with a fluidity that screamed predator. One operator, a woman with a scar running through her eyebrow, took a position near the exit. Another stood by the bleachers. They crossed their hands in front of them, watching. Just watching.

The “audience”—the neighbors who had been laughing at me thirty seconds ago—shrank back. The laughter had evaporated, replaced by a primal instinct to be invisible.

My mother, Commander Zephyr Callister, didn’t look at me yet. That hurt, just a little, but I knew the protocol. Secure the perimeter. Neutralize the threat. Attend to the asset.

Right now, Hargrove was the threat.

“I…” Hargrove squeaked. He cleared his throat, trying to summon his dwindling authority. “Excuse me, but this is a closed board meeting. You can’t just—”

“I didn’t hear you asking for security clearance when you read my service record aloud to a civilian population,” my mother said. Her voice wasn’t loud, but it carried to the back of the gym without a microphone. It was a voice of absolute command.

She stepped onto the dais. The wooden planks creaked under her combat boots. She towered over Hargrove, even though he was standing on a riser.

“You said I wasn’t here,” she said, placing her knuckles on his table. “I’m here now. Clarify your statement.”

“I—we—” Hargrove was sweating. Visibly. “We were merely assessing your daughter’s claims. She submitted an essay detailing… fantastical events. Special operations. Classified missions. We have your record, Ms. Callister. It says you’re a clerk.”

Zephyr reached into the tactical vest she wore over her fatigues. The movement was so fast that the police officer stationed near the door flinched, his hand drifting toward his belt. But she didn’t pull a weapon.

She pulled out a folder. It was red, with a black border. The seal on the front wasn’t the Navy seal. It was the Presidential seal.

She dropped it on the table. Thwack.

“Open it,” she ordered.

Hargrove hesitated.

“Open. It.”

He opened the folder with trembling fingers.

“Read the first line,” she commanded. “Loudly.”

Hargrove squinted at the paper. He swallowed hard. “Executive Order 13-9… Declassification of Task Force Banshee… retroactive immediately.”

“Keep going,” she said.

“Authorization for the acknowledgment of… of the existence of the Naval Special Warfare Female Integration Program… active since 2008.”

A gasp went through the room. I felt the blood rushing to my face. 2008. The year I turned two.

My mother turned slowly, finally looking away from Hargrove to address the crowd. She scanned the faces of the people who had called me a liar. She didn’t look angry. She looked disappointed.

“For fifteen years,” she said, her voice steady, “my existence has been a matter of national security. That meant when I missed a birthday, I couldn’t tell you why. When I missed a parent-teacher conference, I couldn’t write a note. When my daughter sat alone at lunch because the other kids thought she was making things up, I couldn’t call the school.”

She walked over to my table.

I stood up. My legs felt like jelly. Up close, she smelled like rain and ozone and something metallic, like gun oil. She looked older than I remembered from the few video calls we’d had. There were lines around her eyes, gray distinct in her hair.

“But she knew,” my mother said, placing a hand on my shoulder. The weight of it was grounding. “She carried the weight of a classified life before she was even old enough to drive. She told the truth when lying would have been easier. When you called her a pathological liar, she took it. Because I asked her to.”

She looked at me then. Her eyes softened, the steel melting into something recognizable. “I’m sorry, Em,” she whispered, just for me. “I’m sorry I was late.”

“You made it,” I managed to choke out.

“Always,” she said.

“Wait a minute,” a voice called out.

It was Warren Pike. The Vietnam vet was wheeling himself forward again, his eyes locked on my mother’s uniform. He wasn’t looking at her face; he was looking at the insignia on her chest. The Trident. The golden eagle holding the anchor and the pistol. The badge that no woman was supposed to have.

“That’s a Budweiser,” Pike said, using the old slang for the SEAL trident. “You earned that?”

My mother turned to him. Her posture shifted. The aggression vanished, replaced by respect.

“Class 284,” she said. “Though my name wasn’t on the graduation roster.”

Pike stared at her. He looked at the five women standing guard around the room. He looked at the way they stood, the way they scanned the exits. He looked at the mud on their boots—fresh mud, implying they hadn’t exactly taken a commercial flight to get here.

Tears welled up in the old man’s eyes. He sat up straighter in his wheelchair than I had ever seen him.

“I served two tours in the Mekong,” Pike said, his voice shaking with emotion. “I know a snake-eater when I see one.”

Slowly, with great effort, Warren Pike raised his right hand. His fingers were gnarled with arthritis, but his salute was perfect. Sharp. Respectful.

The silence in the room shattered. Not with noise, but with the sheer weight of the moment.

My mother snapped a salute back. “Thank you for your service, sir.”

Pike turned his wheelchair around to face the crowd. He looked furious. “I sat here,” he yelled at the town, “and I listened to you people laugh. I laughed too.” He pointed a shaking finger at Hargrove. “You dragged this girl through the mud. You questioned her honor. And for what? To feel big? To feel smart?”

He looked at me. “I’m sorry, kid. I should have known. The way you knew the jump altitudes… I should have known.”

“It’s okay, Mr. Pike,” I said. And I meant it.

Ms. Winslett, my English teacher, stepped forward timidly. She picked up my essay from where Hargrove had discarded it on the table. She held it like it was a holy relic.

“This…” she stammered, looking at my mother. “This is all true? The weighted ankles? The code words?”

“Every word,” my mother said. “Embry has a better memory for operational detail than some of my lieutenants.”

Ms. Winslett looked at me, her eyes wide. “Embry, I… I’m going to change your grade.”

“I would hope so,” my grandfather’s voice boomed from the back.

The Colonel walked down the aisle now. He didn’t need to run. He walked with the slow, inevitable momentum of a glacier. He stopped beside my mother.

“Thaddius,” Hargrove said, trying to smile. “If we had known… if you had just told us…”

“If I had told you,” my grandfather said coldly, “I would have been court-martialed. And you would have been arrested for possessing classified information.”

He looked at the Board of Education. “My granddaughter has endured your ridicule for three hours. She has been called a liar, a fraud, and a psychological case. She has borne this with more discipline than any adult in this room.”

He checked his watch again.

“It is now 16:20. The press release from the Pentagon went out twenty minutes ago. By the time you get to your cars, every news station in the country will be running the story of the ‘Ghost Unit.’ And they’re going to want to know why the daughter of the unit’s Commander was being publicly crucified in a high school gym.”

Hargrove paled. He realized, finally, the magnitude of his mistake. This wasn’t a school board issue anymore. This was a national incident.

“This meeting is adjourned,” Hargrove announced quickly, banging his gavel. “Adjourned!”

But nobody moved. They were paralyzed by the presence of the six women in black.

My mother looked at Hargrove one last time. “We’re leaving. But I suggest you update your records, Superintendent. My daughter isn’t a liar. She’s a legacy.”

She turned to me. “Ready to go home, Em?”

“Yes,” I said. “God, yes.”

My mother nodded to her team. “Move out.”

The operators fell into formation. My mother put her arm around me—not a tactical grip this time, but a hug. A real, protective hug. We walked down the center aisle, flanked by the deadliest women on the planet, while the town of Mercer County watched in stunned silence.

As we pushed through the double doors into the cool afternoon air, I saw the black SUV parked on the curb. But I also saw something else.

A news van was pulling up. Then another.

“Is this…” I started.

“The beginning,” my mother said, opening the car door for me. “Get in. We have a debriefing.”

PART 3: THE ECHO OF SILENCE

Six Months Later

The rotunda of the Cannon House Office Building in Washington, D.C. echoes differently than a high school gym. The marble absorbs the whispers, making everything sound hushed, important.

I stood before a microphone again. But this time, I wasn’t shaking.

“My mother never asked for recognition,” I said, reading from the prepared statement on the podium. “She only wanted to serve. But secrecy has a cost. It costs families their history. It costs children their parents. And sometimes, the greatest service is allowing the truth to be seen—not for glory, but so that the next generation knows the path is there.”

I looked up. The committee room was packed. Cameras from CNN, Fox, and MSNBC lined the back wall. But in the front row, sat the same group that had been in the gym that day.

My mother, Zephyr, wearing her Dress Blues now, the Medal of Freedom gleaming around her neck. Colonel Thaddius Callister, looking smug. And behind them, sitting in the section reserved for guests… Warren Pike.

He had flown out for the hearing. He wore a new suit. When he caught my eye, he gave me a thumbs-up.

“Thank you, Ms. Callister,” Representative Alvarez said, leaning into her mic. “Your testimony regarding the ‘Family Support for Classified Personnel Act’ has been invaluable. And… frankly, inspiring.”

The gavel banged. But this time, it was followed by applause. Real applause.

The aftermath of “The Incident” (as we called it) had been swift and brutal for Mercer County.

Superintendent Hargrove had resigned two weeks after the hearing. The viral video of him mocking a Navy SEAL’s daughter didn’t play well with the voters. He was currently managing a car wash three towns over.

Dr. Fleming, the psychiatrist, closed his practice after the licensing board started asking questions about his “diagnostic methods.”

But the biggest change was in the house at the edge of town.

It wasn’t quiet anymore.

That night, after the Congressional hearing, we were back at the hotel in D.C. My grandfather was asleep in his room—the excitement had worn him out—but I was wide awake. I went out onto the balcony of our suite, overlooking the city lights.

A moment later, the sliding door opened. My mother stepped out. She had changed out of her uniform into sweatpants and a t-shirt. It was strange, seeing her like this. Human.

She leaned on the railing beside me.

“You did good today,” she said. “You have a better speaking voice than I do. I always sound like I’m giving orders.”

“You usually are,” I smiled.

She laughed. A genuine laugh. “Old habits.”

We stood in silence for a while. The air was cold, but I didn’t mind.

“Do you miss it?” I asked.

She didn’t have to ask what I meant. The adrenaline. The secrecy. The team.

“I miss the clarity,” she admitted, looking out at the Washington Monument. “In the field, everything is simple. You have a mission, you have a team, you have an objective. Real life? Parenting? That’s complicated. There’s no manual for fixing the fifteen years I wasn’t there.”

“You’re here now,” I said.

“Is it enough?” She turned to look at me, her eyes searching mine. “I missed your first steps, Embry. I missed your first heartbreak. I missed teaching you how to drive. I can’t get those back.”

“You taught me how to survive,” I said. “You taught me that panic is a choice. You taught me to breathe.”

I looked at her hands—scarred, strong hands resting on the railing.

“And you gave me something else,” I added. “You gave me the truth. Do you know how many letters I got after the story went viral? From other kids? Kids whose parents are ‘diplomats’ or ‘consultants’ who are never home? They told me they felt less crazy. They realized they weren’t alone.”

My mother swallowed hard. She looked away, blinking rapidly. “The mission was always about protecting the innocent. I never realized the collateral damage was my own family.”

“It wasn’t damage,” I said firmly. “It was just… specialized training.”

She smiled then, wrapping an arm around my shoulders. “Speaking of training. The Naval Academy admissions officer cornered me in the lobby.”

I groaned. “Mom.”

“He says they have a spot for you. Legacy admission, plus… well, you’re kind of famous.”

“I told you,” I said, leaning my head on her shoulder. “Georgetown. Political Science. I want to fight in the room where the laws are made, not in the field.”

She squeezed my shoulder. “Good. I’ve seen enough war for both of us. I want you to have the luxury of peace.”

“But,” I added, a mischievous thought crossing my mind. “I might join the swim team. I hear they need someone who can handle weighted ankles.”

“I can help with the training schedule,” she offered instantly, her voice shifting into Commander mode. “0500 start time. We need to work on your flip turns.”

“Mom.”

“0600?”

“Deal.”

Epilogue: The Truth

Two weeks later, back in Mercer County, I drove past the Community Center. They were renaming it. The Callister Veterans Hall.

I pulled into our long driveway. The sun was setting, casting long shadows across the porch. My grandfather was sitting in his rocking chair, reading a book—my book. The advance copy of the memoir I’d written, the one that expanded on that college essay.

My mother was in the yard. She wasn’t wearing tactical gear. She was wearing gardening gloves. She was fighting a losing battle against the hydrangeas, attacking the weeds with the same intensity she used to dismantle insurgent networks.

I parked the car and watched them for a moment.

For years, I thought my life was a lie. I thought I was the girl with the imaginary mother. But looking at them now—the old soldier and the warrior finally at rest—I realized the truth was simply waiting for the right clearance level.

I got out of the car.

“Hey!” I called out. “Ms. Winslett called. The publisher wants to move up the release date.”

My mother looked up, wiping sweat from her forehead. She smiled, radiant and real.

“Copy that,” she called back.

I walked toward them, the gravel crunching under my feet. I wasn’t the ghost girl anymore. I was Embry Callister. And for the first time in my life, I didn’t have to hold my breath.